A dog is man’s best friend—until a little girl happens along who needs a best friend more.

It was Joe who let him know she was there.

The old dog’s tail began to drum with the slow and steady cadence with which he greeted friends. The man looked up, expecting to see someone he knew. Instead he saw an unexpected diminutive blur, a vague shape in pink shorts and a white T-shirt by the front gate. He took off his reading glasses, and pink and white resolved itself into a little girl hanging onto the pickets.

“I like your dog,” she said. “She’s beautiful.”

At the sound of her voice the old dog pushed his front end backward into a seated position, rose stiffly onto all four legs, and ambled down the path, his tail waving steadily and amiably.

“She’s beautiful,” she said again.

The man considered this. Even in his prime, only true, born-and-bred dog lovers would have gone so far as to describe Joe as beautiful. He was of uncertain ancestry and looked as if he might be a cross between a Labrador who had taken up mixed martial arts and a mastiff who had written his doctoral thesis on Elizabeth Barrett Browning. With something else thrown in.

“Thank you.”

Joe reached the gate and stood gazing at the little blonde face. Their eyes were practically level.

“What’s her name?”

“Joe. He’s a boy.”

“Joe.”

At the sound of his name, the tail began to wave the whole dog. The little girl reached across the pickets.

“My name’s Samantha.”

He laid his book and glasses on the ground next to the empty coffee cup, and he too began the process of working himself from seated to upright, pushing his back end forward to find the edge of the seat.

“Nice to meet you, Samantha.” He really must get some new chairs, something, well, easier. “Where do you live?”

“In Modesto.”

That stopped him, one hand on the handle of his cane, the other braced on the arm of the chair. She was engrossed in stroking the furry boulder of a head in front of her, a boulder that would happily and patiently stand there giving love and taking love until the stars fell from the sky and the planets collided. Or until he heard kibble being poured into his bowl.

“Modesto?”

She nodded. “But we’re staying with my aunt.” She glanced back at the severely unimaginative house on the other side of the street and two doors up.

He had seen the aunt, a relatively recent arrival to the neighborhood, built along the lines of a good cruiserweight—short hair, polite in a brisk, take-no-prisoners manner. He had pegged her as the coach of some girls’ basketball team.

“Oh. Just visiting?” As opposed to what? Moving in? Stealing the furniture? He wasn’t used to talking to very young children, any children. He walked carefully down the path. She was a tiny thing, smaller than her speech, with something curiously ancient about her, a quality of canine patience and forbearance and endurance.

“No. I have to see a doctor.”

“Oh? That’s no fun. I have to see doctors too, but then, I’m pretty old.”

“I’m nine. I have something wrong with my bone marrow.”

“Oh.” He hesitated, uncertain what the correct response to that might be, wondering if he should have said That’s no fun.

“They’re going to try and fix my bone marrow.”

“I’m sure they will. Doctors do all kinds of wonderful and amazing things these days.”

“Can I come in and pat Joe?”

Again he hesitated. Suppose the aunt or the parents objected? Things were so different today, one had to be so careful. He read things in the paper, saw accounts on the news that were as mystifying as they were horrifying, as though the world were no longer the one he had always known and taken for granted. He remembered a small town in Wisconsin and an elderly lady, three or four streets away from his home, who used to let him come in and eat cookies as she told him about the items in the house that caught a small boy’s interest: the framed box of medals her son had been awarded during the war; a cavalry sword hung on display over the fireplace; a picture of two bearded men in uniform on prancing horses, pointing across a river at thousands of men in uniforms all busily killing each other with swords and guns; a small statue of Mephistopheles in red contemplating a human skull; other items, always something he hadn’t noticed before in the Victorian clutter of that old-fashioned house. Who was she? Did his parents even know her? Certainly they didn’t know where he was during those visits, but they were never alarmed by his absence. If he wasn’t at school, he and his friends were all outside in every kind of weather from breakfast until the streetlights came on. What had happened to that world? Where had it gone? What had changed?

“It’s all right,” she said, but he wasn’t sure if she meant it was all right for her to come in, or if it was all right that he wouldn’t let her.

“Sure. Come on in.”

She came in, closing the gate carefully behind her, and as soon as she turned around she leaned forward and gave Joe a kiss on his nose; she was rewarded with a much wetter kiss in return. She giggled and for an instant, just that moment, her ancient face looked like a child of nine.

She hugged Joe, then sat on the bricks with her feet tucked under her. Joe gave her another kiss, then lay slowly down, in sections, until one shoulder and the massive head were in her lap. She ran one hand down his side; the other played gently with an ear.

“He has a big tummy,” she said.

“He does indeed, but then, so do I. Do you have a dog of your own?”

“No. I wish we did, but my mom says I have to get well first.”

“You will. Won’t be long. What kind of a dog will you get?”

“One just like Joe.”

The tail thumped on the bricks.

The man stood, trying to think of something to say next. He and Carol had never had children. A conscious choice: bad parenting examples on her side, an itchy foot on his, an itch that had never gotten scratched. He had grown up with stacks of back copies of National Geographic, an unknown world that danced seductively before his eyes, beckoning: Malta; the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul; the Al-Kadhimiya Mosque in Baghdad, if it still existed; the Great Wall; Angkor Wat; those giant statues on Easter Island. He had once suggested to Carol a motorcycle journey down through Mexico and Central America, along the Andes all the way to Machu Picchu. To his surprise, she was game. They had even bought two enormous Honda Goldwing touring bikes and practiced, cautious, stately jaunts up the 101 to Santa Barbara, then to the wine country of Paso Robles, even, once, all the way to Carmel, but that was a far as they ever went, and they were only occasional and sporadic trips. They never once drove south; always north. The truth is, if you spend your days studying statistical charts, actuarial tables and legal contracts for insurance companies, weighing risk and probability, riding a motorcycle through mountains where cocaine is manufactured by murderous cartels is not a realistic dream. And it wasn’t what he wanted anyway, not really. What he truly wanted, in some hidden recess of his heart, was to ride his motorcycle back to the safety of 1957, or perhaps some vaguely imagined pre–World War Two world where there were gentle discoveries to be made, colorful people to meet who had never seen a television and who didn’t hate America, a world where he could be cheated haggling in a bazaar, not beheaded in the desert. In any event, Carole had started her long decline soon after, and he had sold the motorcycles.

“Does he sleep on your bed?”

The short answer was Good God, no. Joe had gotten increasingly gaseous in recent months; there were times when he considered the statistical probability of the house going up in a ball of flame and would his homeowner’s policy cover canine-caused annihilation. But he defaulted to another, almost equal truth.

“He’s too big. If he slept on the bed, I’d have to sleep on the sofa.”

“When I get a dog, he’s going to sleep on the bed with me.”

“Well, don’t get too big a dog then.”

“I don’t mind. I’ll cuddle up with him.”

“Samantha!”

He looked up. An unfamiliar woman, much smaller than the owner, was standing on the front steps of the unimaginative house looking past him down the street. He raised his hand and when she looked at him, he pointed downward. But by then Samantha was already scrambling to her feet.

“Thanks,” she said. “Can I come see Joe again?”

“Of course. Any time.”

The mother walked briskly down the street and met Samantha halfway, bending down to wipe something off the front of the shorts, probably something left there by Joe. There was a brief conversation he couldn’t make out, and then Samantha headed for the house. He heard the mother call after her, “Hurry, baby.” Then she turned and kept on toward him.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I hope she didn’t bother you.”

“She didn’t bother me at all. And she gave Joe a lot of pleasure.”

The mother looked at Joe.

“Goodness!”

It was an open-ended comment that might have meant anything: how big; how ugly; how beautiful; how old. She too reached across the gate to stroke the white muzzle, and Joe obliged her by kissing her hand with courtly canine dignity.

“Sam’s mad about dogs.” There was a faint accent he couldn’t quite place. Scottish? Irish? Australian? “I’ve promised her one, when she gets well.”

Something turned in his stomach, his body reacting even before his mind caught up. He understood that it was the slight, unconscious emphasis on when, as if by stressing that word she were making a deliberate repudiation of if. He had heard that same stressing of a qualifying word before, years ago. He had made that same stress himself.

“Will Samantha be staying in the hospital?”

“Yes. We hoped to do an outpatient treatment program, but . . .” She trailed off.

“Well, she’s welcome to come visit Joe anytime. If that’s all right with you.”

The world has changed, the world has changed.

“Thank you. It would probably help her a lot. She doesn’t know anyone down here.”

She came the next morning, carrying a stuffed dog, dirty and much the worse for wear. She introduced the stuffed dog to him and Joe—mainly to Joe—as Eubie, and Joe greeted him with much sniffing and the same wet kiss the girl had received.

He asked if the doctors had started fixing her bone marrow.

“No. He just talked to my mom and they took some blood.”

She held out one arm, delicate as a twig, and showed him the band-aid on the inside of her forearm, just below the elbow.

He remembered Carol at the end, the tubes taped to her bruised and riven skin, the breathing apparatus, the monitors, her eyes trying to smile at him out of a cocoon of modern science, the flickering light of the television that stayed silently on around the clock, the soft sound of bells, the background din of voices in the hall, the smell of antiseptic and food no one would eat, the bustling nurses, the constant quiet hum of busyness no matter what the hour, the impersonal smiles, impersonal, impersonal, impersonal . . . Jesus. It had nearly killed him; what would it do to this little girl, to her mother, if it came to that?

As if she was reading his mind, she said, “I’m going to live to be ten.”

Caught off guard, he fumbled. “Oh. Ah, is that what the doctor said?”

“No. That’s my goal. I want to live to be ten because it has two numbers in it. One and zero. Nine only has one number and I want to have two.”

“Oh, well I’m sure you’ll manage that and a lot more. When do you turn ten?”

“Next year. I had my birthday last month.”

“Happy birthday, a little late.”

“Thanks. I had a cake and all my friends came over . . .”

She began to list them, the names of friends in Modesto, presents given, games played. She had wanted to go to an amusement park, but it had been deemed too dangerous given her bone marrow, but her mom had made it a great party, and Alissa had brought her dog, so there was a star attraction there, even though Alissa’s dog wasn’t as beautiful as Joe.

After she left for the hospital, the mother waving to him from up the street, he sat in his chair on the porch, drained, too tired to read. He was too old for this, the emotion. He didn’t know what to say to a healthy nine-year-old, let alone one whose ambition was to live to ten. He wished he could just give her a kiss and wag his tail and let her play with his ears.

She came for four more mornings, and he found it was easier than he expected. She was never able to stay long, sitting on the ground or on the steps with one hand on Joe, and she kept up a steady stream of chatter he found oddly soothing; it was directed primarily at Joe in any case. He didn’t have to say much; instead he listened and made what he hoped were appropriate interjections at appropriate places. Mostly, she talked about Modesto, her school, her teachers that she especially liked—English was her favorite subject because they got to read stories and the homework consisted of reading books; she was reading Charlotte’s Web and she loved it and was going to read it all over again as soon as she finished—her friends at school, a friend at the end of her street, her friends’ dogs, her father who was in the Army, but he was going to come back from somewhere overseas . . .

The mother had taken to calling for her from the front steps of the aunt’s house, waving to him, and after they left for the hospital he would sit and wonder at the vital stream of words, of life, that came pouring out of that fragile little body.

Santa Ana winds made reading on the porch too much like an athletic event, so he stayed inside for two days. He looked out the window for her, but she too seemed to have been blown inside; he never even saw her on the front step of her aunt’s house. When the winds stopped, he and Joe took up their respective places out front, but the little girl didn’t reappear. He didn’t even see the mother or the cruiserweight aunt.

Then one afternoon he was standing in the open garage, taking groceries out of the trunk. He had one bag out and was bracing himself between car and cane, contemplating the two steps to be negotiated up into the house, trying to catch his breath before tackling the climb, when Joe turned around and began to wave his tail.

The mother was walking up his driveway. At first he thought he must have done something wrong, said something inappropriate. Her face was set and rigid, her eyes hard, a bad actor registering anger. She slowed slightly to run her hand over Joe’s head, then walked up to him.

“Sam would like to see Joe,” she said. Her voice was carefully modulated. “The thing is, it will take some doing.”

“Some doing?”

“Yes. He has to have all of his papers, from the vet, you know, showing he’s up to date on all his shots and vaccines.”

“Oh. I have all that. I have his records and papers and everything.”

“And he has to have a bath.”

As if he understood the words, Joe looked up at him as he looked down at the old dog.

“Oh. Well, I suppose we can get that done. Is Sam in the hospital?”

“Oh. Yes. I skipped that part. Sorry.”

“How is she doing?”

“Not well.” It sounded like a door slamming on anything he might have said, and before he could think of anything, she drove on. “Tomorrow afternoon . . . If you can do it, tomorrow afternoon would be best, between one and four.”

She handed him a little card. It had the name and address of a hospital on the other side of town. On the back was a miniature map with the names of freeways and avenues he couldn’t make out.

She had turned her head and was looking resolutely away, down the street, perhaps all the way to a distant hospital room.

“Yes, of course. I’ll be there. Joe and I will be there between one and four.”

She spun around without speaking and walked quickly back to the unimaginative house.

The groomer’s waiting room smelled strongly of something much too sweet; not unpleasant, exactly, but just too sweet, too heavy, too much, and when the girl brought Joe out he smelled of whatever it was. They had painted his nails with some polish that had little specks of glitter in it so that he looked ridiculous, an ancient heavyweight fighter in spandex and a tutu. The man said nothing, but took the leash and turned for the door.

“Oh, by the way,” the girl said, and he turned around. “When Odell picked him up, he—”

“Who?”

“Odell. Joe is so big I couldn’t lift him, so Odell put him in the tub, but when he picked him up, he gave a little sort of yelp, Joe, I mean, and when I was washing him I felt a sort of, like, a kind of something in his tummy, back here.” She ran her hand over Joe’s flank and was rewarded with a wave of tail. “You can feel it.”

He ran his hand over the flank and felt the swelling under his hand, under the smooth clean coat, a shallow convexity, hard and ominous.

“Thank you,” he said. “I’ll call my veterinarian when I get home.”

But he knew as he said it that it was ridiculous. A dog this big, thirteen years old . . . What could be done? What can ever be done after a certain point?

The hospital was uncomfortably stuffy, humid somehow, as if he were outside in Alabama. A lady at the admission desk looked at Joe as if he were something that offended her personally. She asked who they were going to see and demanded the veterinary records. She gave him a floor and room number and directions to the pediatric wing. It was a long walk down a wide corridor made narrow by its length and by the endless line of gurneys, wheelchairs, stainless-steel carts, food trays, cloth laundry containers, and things he couldn’t identify cluttered along the walls. Twice he stopped, leaning on his cane, Joe sitting heavily and clumsily on the slick floor. They went on to the elevators.

The pediatric floor was cooler and the walls were covered with brightly colored cartoon characters he didn’t recognize. He looked for Bugs and Daffy and Mickey, but saw dancing flowers and a yellow dog that looked like a demented Great Dane, a mermaid with red hair, creatures he couldn’t identify, and because they were all so foreign, he felt increasingly out of place, as if at any moment someone might direct him to the geriatric floor.

But Joe acted as if this particular floor of the hospital was the place he had been waiting for, as if his life had been building to this moment among strangers. Some of the stiffness seemed to have gone out of his step and his tail waved magnificently, indomitably, as he beamed from side to side at children being pushed in wheelchairs, at nurses hurrying past, at a man in golfing clothes who observed him from a doorway.

The reactions were unpredictable. Some people stared blankly; a nurse veered away from them; some people smiled; a doctor watched them with something very like fear.

And then they were at the room. The door was ajar, but he tapped on it and someone called, “Come in.” A nurse was standing at the end of the bed and her eyes went right to Joe, her mouth opening into an O. The mother was seated in a chair in front of the window. Beside her was a man in a Hawaiian shirt, his hair cut so short he looked bald. A television on the wall was playing, flickering lights and happy music.

Sam was in the partially raised bed, so tiny, almost invisible behind the machines, the monitors, the IV stands, the tubes, the sheets, the tray stand, the paraphernalia of life and death, and for a moment he was disoriented, as if Carol had somehow reverted to childhood, and he was uncertain where he was, who he was visiting.

No one spoke, but she turned her head slowly, so slowly. He had to make an effort not to flinch or recoil, the little face had aged so much more. And her eyes! The eyes that had been so bright were dull and glazed, and when she looked at him he had a sense that her gaze was unfocused, that she might have been looking at something past him, or perhaps not seeing him at all. But something, not her face exactly, and not her eyes, but some other part of her—a foot, perhaps, or a shoulder, maybe a hand—seemed to recognize him, and her eyes dropped slowly to Joe.

And as if it were the most natural thing in the world, the sole thing he had ever been trained to do, the old dog moved forward to the side of the bed and put his head on her chest, just below her chin, nose to nose, dim eyes gazing at dim eyes, two ancient faces, each content to give love and take love until the stars fell from the sky and the planets collided.

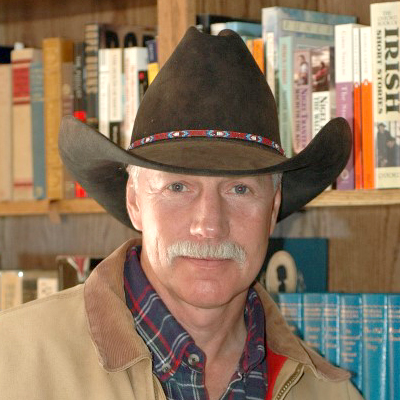

Copyright © 2018 by Jameson Parker.