To some, a train might signify adventure, or romance, or industry. What does it mean to a soldier fresh from Vietnam?

The night of the train, I rode home from Vietnam on a nearly empty Greyhound bus to the freezing dark of my northern Wisconsin paper-mill town. The bus left me off on the highway at a Texaco station—the only station for twenty-five miles.

Once I got off the bus, I could smell the rank, sulfur-laced Mill towering in the distance. Its lights shone above the dark trees at the edge of town like helicopters hovering in attack formation. I looked both ways down the forested road.

I’d returned to see my high school friend, John. Both of our families, which weren’t very large in the first place, had emptied out of our mill town before we left high school. Parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, all in prison, at another mill somewhere, or dead. John and I, both loners, became friends in high school. He hunted and fished far from others whenever he could. Sometimes he’d skip school and go off into the deep woods for days. I read adventure stories day and night, sometimes skipping school too, and dreamed of getting out of town.

I walked the mile into town to his apartment—he half-smiled when he opened the door and said, “You’re a little thin.” I’d lost twenty pounds the month before I’d left the war to the dysentery that nearly killed me. I wondered if others could see a green tint to my face.

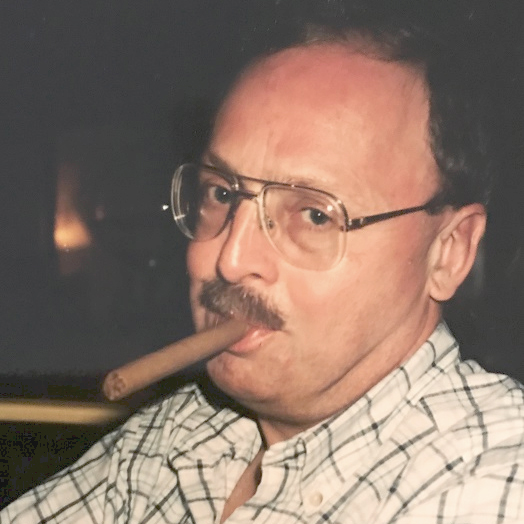

Working at the mill had already made John look ten years older than he was. He’d grown a full beard, wore wire-rimmed glasses, and was bald. But he was still barrel-chested with arms like pine-tree trunks.

We picked up his hopped-up, refurbished British racing green ’59 Chevrolet and two six-packs and headed fast out of town on empty red granite back roads, drinking and spinning and swerving around corners, blowing the granite out from under the wheels like double-barreled shotguns. Finally, we found a parking spot on an old logging road and idled the car for hours. I told stories and he said, “Yeah,” “I get it,” or “Sure, sure, right.”

Mostly, I didn’t tell him about bloody, sucking chest wounds, empty, lifeless eyes, or twitching limbs. Instead, I told him about the emaciated ten-year-old Vietnamese girl whose life I saved by giving her blood, the tube running directly dark red from my arm to hers. She and I lay there together for what seemed like hours. We couldn’t understand each other, but later she finally got it across to me that I would be her brother from then on.

Or I told him about our unit spending hours in the burning Asian sun building an elementary school out of crate wood for the village next to our base camp when we were on downtime. And then I told him how we put a sign up after we finished. THE VILLAGE BASE CAMP ELEMENTARY SCHOOL. The sign was in English.

Or the time on patrol in this dense, God-forsaken jungle mountain area where we came upon an abandoned Buddhist temple, four concrete buildings that had been bombed and strafed until only one building stood with a partial roof. We found twenty men and women chained to a wall inside, mental patients the Buddhist monks had taken care of but had abandoned when they were driven from the place. We didn’t know what to do with them. If we tried to get helicopters to airlift them out, we’d be laughed at. So we unchained them and let them go. After all, as our lieutenant said, we had a war to fight.

John and I finally returned to town just in time to buy two more six-packs. Then we headed back toward his place. Suddenly he stopped in the middle of the dark empty street and pointed his car toward the Mill, the only lit and living thing in town, like a monster consuming the rest of the light, chewing up lives—the Mill, trains emptying and filling with pulp wood, moving by every fifteen minutes like the end of time. The Mill.

The car rumbled and thick steam rolled off the hood in the frigid air, forming icy shadows. Mill smell reeked in the car. We could hear the train banging the tracks towards the intersection ahead. I could make out John’s eyes wide in the dark, searching for me to know what we should do next.

“Hit it!” I shouted. He stomped on the gas pedal like trying to break through the floor. The car roared and swerved and fishtailed the two blocks to the tracks, the train light looming above us as we crossed over.

We nearly made it, but the train hit the back end of the car and shoved us around three times like God had reached down and spun the car like a top for the amusement of a group of children. We blew all four tires and ended backward on the side of the street in front of old Miller’s Hardware. The left rear side was smashed in and the back window was broken clean out, like someone had taken a baseball bat to it.

We got out of the car and I looked at John. He just shrugged so we did the only thing we could do. We dug the two six-packs out of the back seat and walked the ten blocks back to his place in the empty dark.

Copyright © 2018 by Rick Christman.