In the wilds of Upstate New York America, a Belarusian immigrant finds himself torn between the ideologies of family, Joseph Smith . . . and lo-fi indie rock.

Originally published in Glimmer Train, Spring 2011. Guided by Voices lyrics by Robert Pollard.

June 6th

Boris feels a mosquito somewhere on the back of his neck. It is about to bite him and he is going to let it. “Go ahead and bite me, Ulster County mosquito!” At least he is getting some attention. Marina doesn’t bite him anymore the way she used to, not since he was laid off from the town’s only erotic antiques shop a few weeks back, and not since the doctor said the operation to fix Sasha’s strangely inverted rib cage (pectus excavatum) would not be covered by Medicaid.

A great time to come to America, right in the heart of an economic disaster. Marina keeps reminding him of this while giving him the “I told you so, and it is even worse than that” stare. Boris tries to reduce the amount of time he looks his wife in the eyes these days. Her otherwise gentle green eyes would threaten; the irregular blood spot in her left eye would swell, having the effect of a magnet ripping at Boris’s soul.

He is sitting on his American porch on a Walmart lawn chair sipping his all-American pink lemonade. He first imagined this lifestyle after seeing a Tom Hanks movie with lots of beautiful Victorians and Eden-like porch scenes. The dream of American relaxation.

Marina is putting Sasha down. She will be out in a few minutes to blow dry her wet brassieres, which are hanging across a wire on the far side of the porch, just above the bag of charcoal she stuck a chain through and locked to its base. Marina simply doesn’t get America. She doesn’t care, but for Boris having his laid-back neighbors see this metal chain protecting their charcoal bag is a great embarrassment. “Laid-back.” Boris repeats this new expression he recently learned. There is no translation in Belarusian for laid-back.

Marina doesn’t understand the big picture. Boris Mosheyev, twenty-nine, of good character and energy, with Slavic discipline and persistence, with a solid education in computer information systems behind him, with the power of his mother’s love, and the transcendent tunes of Guided by Voices as the soundtrack of his life pushing him forward daily, will make it in Upstate New York America. This he was told in Minsk by a Gypsy woman his Baba Sveta swears by. According to Grandma Sveta, this particular gypsy has never been wrong.

Marina steps out from the living room with the blow dryer plugged in through the window. He can’t help but look at her. She is making the blow dryer wet with her dripping hair. Now she speaks.

“The humidity of this place. I’ll be surprised if it doesn’t kill us.”

And Boris, sweating into his glass of lemonade, can already hear her next comment, waxing nostalgic about the glorious conditions back home. Then, predictably, her soft mouth forms the words. A perfect replica of what just played out in his mind.

“In Minsk, it gets warm, but the air is nice and dry.”

He wants to tell her now, again, that she doesn’t get America, but then she will get upset and perhaps lose her concentration and burn her set of brassieres, which they cannot afford to replace. To raise her spirits, he can share with her the two bumper stickers he saw today on his way down the hill from the unemployment office. One read:

GOD IS COMING . . . AND BOY IS SHE PISSED!

The other proclaimed: PEACE AND LOVE TO ALL THE PEOPLE OF THE EARTH (WITH THE EXCEPTION OF RIGHT-WING PIGS WHO CAN KISS MY ASS!)

“You know,” she says over the sound of the blow-drying machine, “We don’t have enough to meet the rent tomorrow.”

There is no public expression of bumper stickers in Belarus. If you upset anyone in public, written expression on your auto, someone will simply smash your windows in.

“Let me tell you again about John Smith, Marina. Marina?” And now Boris stands up, grabs the blow dryer out of his wife’s slim fingers, switches off the power, and places it down on the round porch table under the Smirnoff umbrella his brother Yuri smuggled out from some Black Sea resort and shipped over as a housewarming gift. Marina reaches down and picks the blower back up.

“I don’t want to hear any more about these Mormon people. I told you this,” she says and powers the blow dryer.

Boris considers his home. The rotting wood badly needs a paint job. Their place is at a dead end next to the neighborhood dumpster. He was recently over to a delicious barbecue at the home of Doug, the local Latter-Day Saint cohort leader. Doug and his wife have a large, beautiful maroon-shingled Victorian over on Beaver Way. They have enough space for a small playground and pool in the backyard.

Boris wrests the blow dryer from Marina’s hands and pulls the plug from the socket. “John Smith . . . no, no. I mean . . . Joseph Smith is not a prophet.” Boris, facing Marina, his desperate, tired eyes just a few inches from hers, is using the full weight of his slight upper body to bring home his point. “No, he is the writer of the Good Book, you see. This is American kind of religion. It is something more honest and beautiful than Orthodox. In Ohio . . .” But Marina’s familiar stare makes Boris lose his train of thought, as does the sweet smell of the narcotic popular with American hippie types wafting from the upstairs window of Sage, his landlord. Boris worries that the smoke will infect Sasha sleeping in the back room, that little Sasha will suffer more from this than he did from the generally contaminated Minsk air he had become accustomed to back home.

“You see, it is nothing like the Orthodox faith. Nothing. This is a pretty new American religion. No icons, no hocus-pocus holy smoke. Joseph Smith is a modern savior. This is what Doug and Gregg are saying, Marina!”

Marina turns away and is gone. She has slipped back inside to check on Sasha. Boris feels his neck going stiff and a mosquito crawling up the leg of his shorts toward his ass. They have been fighting on and off (mostly on) since their arrival as “political refugees” two months earlier.

Boris slaps the attacker. He feels a burning sensation in his neck. The silence of these long nights is making his blood pressure rise. If Marina can just stop and, for a moment, not see the world through her dead-end Belarusian lenses, maybe she will be able to recognize opportunity knocking. This is the new world, not backward, medieval Minsk. He slams his lemonade glass against the Smirnoff umbrella in frustration.

Shortly later, she steps out with a piece of Ukrainian rye and a glass of kvass.

“They are a cult, Boris. Idiots! What is this, no caffeine? We love the taste of Diet Coke. What kind of God forbids cola, can I ask?”

Doug has hinted that he has connections in the world of “financial services” and that he can “hook Boris up,” one brother to another.

“Fucking forget about the caffeine part of it, Marinusha. Spasiba! Stop judging my every move. Trust me, these are good people. We need this support now. We need to do something. Doug has plans for us, for Sasha’s pectus. Lots of good ideas. He likes my Twitter accessory invention. He invited us again today to come be tenants in his place.”

Boris doesn’t have to remind her about the playground and swimming pool part of the deal. She is well aware of the details. His mother always says that Marina is the practical one among them.

“Doug said that?” Marina sips her kvass. There is no one around, no movements. Boris thinks he might hear a squirrel running behind the dumpster.

“Da, he did.”

Boris takes a deep breath of Catskill mountain air. It is the absence of certain imagery in the stillness of the fresh mountain air that confuses his soul in certain off moments. The absence of smoked Baltic fish in every cabbie’s glove compartment, the saltiness of it defining the cab ride. The absence of the salty, rude language of his Druzba neighbors, their lips that enclose their nicotine-stained teeth always going on and on about how much they suffer, day in, day out. A competition of suffering, that was what their Druzba neighborhood was all about. The absence of constant scheming of how to obtain this by doing that and who knows who you need to know to be able to get to do who knows what.

No, here in Upstate New York America people play it straight. They even volunteer to help others with no shady motive. Marina doesn’t get that the old Irish lady next door, Molly, drove him to the Chamber of Commerce and patiently helped him fill out the job search form correctly, simply to be nice, simply to be good.

The problem isn’t the people; the problem is that they came to Upstate New York America at the wrong time. Boris often watches the articulate black politician on their little black-and-white TV and has a notebook page full of new and timely vocabulary terms: bailout and bankruptcy, foreclosure and eviction. Molly shrugged in dismay when the folder she told him about full of job opportunities at the Chamber of Commerce office had thinned down to six job descriptions, three of which involved cleaning up road kill on Interstate 299.

“Even the Mexicans are leaving town,” Molly said. “Things ain’t like they used to be.”

Boris turns to Marina now, who is lost in thought, mindlessly swatting flies with the remaining crust of her rye, and covers the nape of her neck with his open hand, his sweaty fingers caressing the tips of her short brown hair.

“All I’m asking is that you think just a little about the sacrifice of John Smith.”

“Joseph was his name, no?”

“Joseph Smith, not John, da. Think about this and we will see.”

“Yes,” and now Marina can hear Sasha’s irregular breathing, a product of his inverted rib cage condition, which plays out at one point every night. “I will think more about this Joseph Smith American.”

May 20th (two weeks earlier . . .)

Let’s ride on airplanes and buses

Let’s ride to the end of the line

Let’s ride on fast motorcycles

Let’s leave the routines of living behind

Boris walked up the steep Main Street hill toward the erotic antiques shop singing at full volume along to his favorite Guided by Voices tunes, as he did every morning. He had the iPhone playing his GBV favorites. The hippie types, young and old, would wave and flash their big American smiles at him, say things like “Peace out” or “Sing it, man.” What was there not to love about this town? He had a job. Marina’s list of kids interested in piano lessons was growing. Sasha loved kindergarten, macaroni and cheese, and the friendly American kids who didn’t mind that he couldn’t understand a word of English.

Boris had memorized the words on the historical marker up the hill, and he sang them out loud to the tune of the GBV song in his ear.

Founded in 1678, da da!

On the shores of the Waikill river, da da!

When he told locals he was from Belarus, to their raised eyebrows he would say it means White Russian in English, and people would smile, as Americans did for no apparent reason, and inevitably say, “Like the Kahlúa drink, right?” This happened again and again until Boris would simply add when he introduced himself that he was a White Russian, named after the mixed drink.

He passed Sage, his young landlord and boss at the shop, sitting on the ground in front of the Muddy Cup café, smoking a clove cigarette in the morning sunlight. Boris was both impressed and perplexed at Sage’s consistent ability to remain relaxed and cheery. Sage wore the same purplish-greenish tie-dye T-shirt every day, and had a ring through her nose. Only in America, Boris thought. This is freedom! His wife would never get it.

“Hey, GBVs”—this was Sage’s nickname for him. “Give me ten. I’m gonna smoke and chill. There aren’t too many people waiting on line for us to open anyway, right?”

Boris nodded. In fact, it was Wednesday, and they had sold only one item this week, a flour tin decorated with a print of an Indian prince and a member of his harem in various Kama Sutra–like positions, and this item had been returned the next day. School was out and the SUNY students had deserted the town. This didn’t help. Boris looked up at his favorite piece in the window display, a wooden sculpture of an American Indian woman masturbating, next to it a selection of antique love beads. He continued up Main Street toward Beaver. Perhaps with these extra free minutes he could steal a nice peek at the mountains before spending the rest of the day inside the shop doing nothing.

At night Marina strangled him with talk of chores and financial responsibility, but the mornings were his. He could sing as loudly as he wanted to sing, and people would just smile.

Coded ancient, Oh brightness we shall see

Loaded up and at night when we shall flee

Not to tread through the heavy life

Sink in the dream

When local business owners made comments about the recession and the decline in business, Boris would put on his best American smile and say, “In Belarus, always recession. Always recession there. I used to recession. The America recession no problem for Boris.”

He looked back as he turned up to Beaver to make sure Sage hadn’t moved from the sidewalk. His brother Yuri had sent him the iPhone, and later an iPod as well. Last he heard, his brother was scheming up and down the Black Sea Coast. A year earlier, Yuri had gotten a Bulgarian Mafia leader’s wife pregnant. Always been dishonest, Yuri. Mostly dealing in stolen I.D.’s these days. It was easy to make money in this way. Anybody could steal. It wasn’t Boris’s fault that he was poorer than his younger brother. His mother wouldn’t hear it. “It doesn’t matter, Borcho. I love you just the same, money or not.” But the question remained: How could he send as much money home to mommy as Yuri did?

There was only one bench on Beaver Street, offering the most wonderful view of the open mountain range to the north, and no one ever sat in it. In Belarus, there would be an old babushka plopped down on the bench and you’d have to wait a week for her to get up, and when she finally did, there’d be six more impatient babushkas behind her ready to fight it out for the seat.

Boris decided that this was a good moment to send a tweet to Didem in Brighton Beach.

How is it go, sweetie? I hear new expressions. The gravy here used be better. The grass greener in good conditions. Ciao

He loved Twitter and had some business plans to cash in on a Twitter accessory he had invented. He just needed to save up some money for a good copyright attorney. Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s creator and one of Boris’s all-time heroes, was a true American entrepreneur, a real original. Boris couldn’t think of one Belarusian comparable to Dorsey.

Boris had met Didem, his Turkish friend, online, and now they exchanged daily tweets, some more intimate than others. He had not mentioned the existence of Sasha or Marina, of course, and didn’t plan to. Glenn and Linda, the host family that had taken them in upon their arrival in America, had promised to take them to New York City one weekend, and he had hoped to slip away to Brighton Beach for a few hours alone to meet his Twitter pal. This was before everything had fallen apart. Glenn and Linda’s business had gone under just about the same time as the tragedy, and Linda had had a nervous breakdown, leading to her separation from Glenn and the dissolution of their status as refugee hosts. Since no local family would take in the Mosheyev family in the difficult economic climate, he and Marina were left to their own devices. Luckily, Linda had connected them to her friend Sage who had offered Boris a job, and soon after a cheap place to rent.

Boris checked his latest tweet.

Boris, I would like you to visit me on the beach.

It made his heart sing, an intimate tweet from Didem! He checked the time on his iPhone. It was time to try to get back to not selling antique dildos and aphrodisiac candles.

On his way back to work, Boris noticed dark clouds rolling in from the east, and his thoughts turned from the promise of Didem to the fate of Linda and his host family.

Linda was five months pregnant when he arrived in Upstate New York America with Sasha and Marina. Part of the unofficial deal was that in return for hosting the Mosheyev family, Marina, an experienced mother, would help out with the new baby. Their freshly painted room upstairs was adjacent to the baby room–in–progress.

From the start Boris had felt a special something for Linda. Twelve years older, she was like the big sister he never had. She showed she cared by patiently tutoring him with his awful English, showing him all the best places for a five-year-old to enjoy in this hippie mountain town so foreign to the Mosheyevs, and by helping to soothe his fears of being too culturally inadequate to succeed in his new life. Linda was a social worker by trade and her upbeat spirit was enough to lift three lost Slavic souls.

But this had all changed.

Boris had a one-minute memory clip of Linda, as vivid as any from his entire life. The clip replayed any time Boris’s mind was, for whatever reason, drawn to push the replay button, and now, as the sky burst open with the first pelts of rain, Boris pushed replay. Linda, her hair disheveled, her eyes bloated bloodshot red, was at the kitchen sink in her dark blue bathrobe peeling potatoes. Boris entered and she turned to him.

“We gave her a name, Boris—she had a name!”

A week later, Linda was gone. Glenn said she had moved back home out west. Soon after, the house foreclosed and Glenn disappeared as well. Linda had left Boris a short note before vanishing. She was sorry about failing him, and his family could move in with a friend of hers named Sage.

A few hours later, after stepping out of the rain and into Sage’s shop, Boris became a real-life, living example of the statistics he had been reading about over and over in the free newspapers left near the door of the Muddy Cup.

Laid off.

Sage offered him one month free rent.

“Hey, man, it’s like I don’t have any customers, so I kinda don’t have any money to pay you.”

Boris tried hard not to look down at Sage’s perky, braless American breasts through her tie-dye as she fired him.

“I work good. I have little child, Sasha. He need pectum surgery. I need money.”

Back on the lovely and free American bench at high noon, he tweeted.

Didem, maybe I soon coming to your beach

May 28th (8 days later)

There was a strange morning light; this he would remember well later on. He walked in the dead middle of the street, too early for cars or other pedestrians to be out. Boris had had a big fight with Marina the night before about money. He saw a bumper sticker he liked on an old beat-up Volkswagen bug, SUCK MY BAILOUT, and quickly wrote it down in the little black notebook his dad had given him the year Lukashenko had taken over and destroyed their country. He had a habit of taking down every interesting overheard expression, every provocative new linguistic item in the notebook his father had once used in his work as a state trolley ticket checker in Minsk. Boris had inherited the half-full notebook when his father died, and he would exercise his American freedom in this space that was created for tallying the names of Belorusians who were in violation of not paying their trolley fare. Each page in the book had a names and date column.

| 23 March, 1994 | |

| Yulia Shemenkova | 17:23 |

| Valerie Gaperin | 09:23 |

A very tough job his father had, chasing down those who risked getting a stiff penalty for riding ticketless. An honor system in a very dishonest system. His father had dropped dead just a week before Lukashenko had reimposed martial law. In Minsk, people just died. They didn’t need a reason. It could be the heart from too much stress and sausage, or the lungs from constant smoking and continuous inhalation of industrial contaminants, or more likely a heart-lung combination. Fifty-seven years old. A half-Jewish, half-Orthodox trolley worker who believed in nothing, except perhaps that one should always pay their fare.

Boris scribbled down the beautiful bumper sticker words. No one around, he walked down a steep hill in the middle of the street. Boris was speaking to himself out loud, trying to figure out how to meet the bills. Con Edison, Verizon . . . what others? He was asking the light winds and the chirping sparrows if they had any suggestions. Some advice on how the Mosheyevs could stay afloat, could keep paying for monkey yogurts and corn muffins for Sasha and still have enough for the rent.

The sun was coming through two sets of cloud formations. There was a burst of deep yellow framed in rich orange light, behind this a hint of sky, the promise of blue. It was an act of bravura, magnificent to behold, reminding Boris of the light off the Danube at dawn on a sailing trip he had taken one spring with Yuri and their father. This had been his one and only childhood trip out of Belarus, and Yuri had nearly been arrested the day before for lifting a Hungarian cheese pie from a street cart.

Boris squinted as he tried to squeeze a layer of meaning out of this natural phenomenon he was witnessing on this insignificant Upstate street.

Boris was ripe for something new. He sensed a growing void in his life. Yuri the thief was raking it in, living it up, and winning all kinds of points with their mother for sending her the cash she needed to survive. His mother knew better than to credit a thief. She was a veteran schoolteacher of Russian and had resisted the temptation to sell grades to the highest bidders. Grade bribery was common practice in Minsk, but she wanted nothing of it, and for her moral stance she was dependent upon her sons to pay the bills.

The hill was so steep that Boris had to brake with his knees so as not to stumble. Such a hill would cause traffic and pushcart accidents in Minsk. What was he doing up so early anyhow? He had no job to show up on time for. Was he simply hiding from Marina’s judgmental gaze? He stared up at the light and thought about his life as he braced his way down.

Boris had been drifting those last years in Minsk, wondering how he could protect young Sasha from the code of corruption that increasingly defined his culture. One fall day, in fact on the ninetieth anniversary of the October Revolution, Boris had been apprehended for his obsessive note-taking by a government agent in a gray state jacket. He had been kept in state custody until a balding state agent who smelled of homemade vodka deconstructed his jottings and came to the realization that they mostly described the particularly large chunks of shit left by a passing wild mutt.

Back home, there was no moral code.

A car horn broke the perfect silence and brought Boris back from Minsk to Upstate New York. That was when he saw them, three men in dark black suits ascending the hill. They were, like Boris, walking in the middle of the empty sun-soaked street. Boris continued his descent as the trio of men walked in perfect formation, side by side, up the hill toward him. It became clearer and clearer to him as they grew closer and their classic American features came into view that he was their mission. They weren’t just coming toward him. They were coming because of him. He was what they were walking toward.

The men were nearly upon him, smiling and waving. Later, when they had identified themselves, Boris would remember the case a few years earlier when Lukashenko’s police had expelled two American Mormons from Belarus for “illegal missionary activity.”

He met the three strangers halfway down the hill with the strange light bouncing off their perfectly ironed white shirts and the little black books in their arms, Boris holding his own little black book.

“Beautiful morning, beautiful light.” The tallest one, with blond hair, blue eyes, and a tender voice, spoke first.

“Yes, it is so.” Boris nodded, flashing his imitation American smile.

He wondered what these guys who dressed so formally at dawn were all about. But this was how Marina saw the world, always with suspicious eyes. Boris wouldn’t take the cynical path. Maybe they were just nice fellows, like so many others he had met in Upstate New York America.

“Where are you from? You sound like you’re not from around here.”

“I from Belarus. White Russia, like mixed drink.” Boris laughed, but was beginning to get tired of the joke.

The shorter, very well-built guy standing in the middle spoke. His arms were straining against the fabric of his suit.

“Well, we don’t drink alcohol, but . . . Belarus, well that’s just awesome.”

“Awesome, yes.” Boris looked around, down the hill, behind him up the slope. No one.

“Well, I’m Doug from Utah, and this is Gregg and William.” Boris shook all of their hands. They offered firm handshakes.

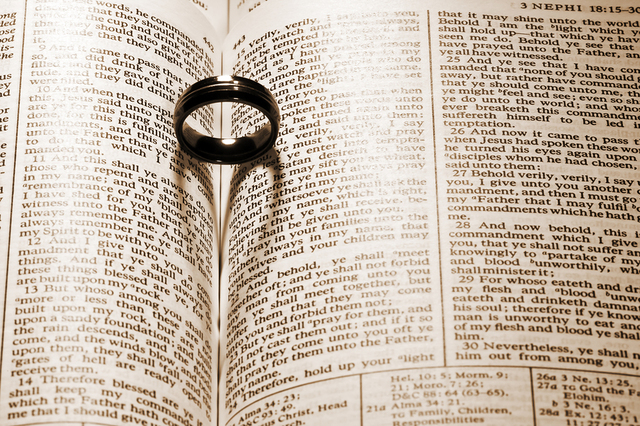

Doug placed one of the black books in Boris’s hand.

“Have you ever heard of the Book of Mormon?”

. . . and that is how it started.

June 26th (about a month later)

“What people don’t understand is that we can be hip, too. Keep that in mind, Boris, and don’t get frustrated.”

Doug wipes the sweat off his white starched collar.

“Don’t you worry, Doug.” Boris shrugs, looking back at the disapproving tattooed mothers and goateed skateboarders who are shutting the gate hard behind them. “Tomorrow another day. Better.”

This is the first time Boris has been asked to do missionary work in his own neighborhood. They had just been kicked out of Gravel Head Park by some hippie-type young parents. Boris recognizes Layla, one of the cashiers at the Muddy Cup, and is ashamed she has to see him like this: a cartoon character with these more sincere, clean-cut, real Americans flanking him.

They had walked through the gates into Gravel Head, keeping their smiles constant as they passed town youngsters smoking narcotics, teenagers half naked on top of each other up the grassy hill, and a pair of lesbian mothers watching their kids in the playground. All sins according to the Book of Mormon. Boris did his best to wear a “pleasant expression” at all times. That was what Elder Timothy had taught him at the MTC. Boris, Doug, and Gregg hadn’t said a word beyond, “Good afternoon,” and folks were already making very negative faces at them. The key to it all, Boris remembered from his two weeks at the Missionary Training Center in Poughkeepsie, was to “do good” and others would “welcome in the Lord’s spirit.”

Boris had come with a black plastic bag with a mission to clean up littered beer bottles and reefer butts from the lawn. Gregg and Doug were doing the same on the other side of the playground.

A bearded man wearing four earrings and a black T-shirt with SUCK MY D— CHENEY written on it got up as Boris approached with his bag, and the man gave him the finger before exiting the park. All of these negative stares and suspicious looks make Boris nostalgic for home. This was exactly the way people treated strangers in Minsk. Strangers could only mean problems. Yet, this was the first time he had not been greeted in a friendly, laid-back way in Upstate New York America, and it made him feel discouraged. It was a beautifully sunny afternoon in the park with a “live and let live” feeling in the air (he loves this term, “live and let live,” and has written it in his notebook), and here came Boris, way overdressed in a stupid suit when everyone else was wearing shorts and T-shirts, and now he and the elders have been told to “get lost,” and have been banished from their own neighborhood park.

Boris and the elders walked down the hill toward Gregg’s SUV.

“Why don’t we call it a wrap for today and head back to the MTC?” Gregg says.

Gregg, who stands two meters high, confessed to Boris during Boris’s first day in the field just a few days earlier that he is a recovering glue addict, and blew a chance to play professional basketball due to his habit. “The Elders saved my life. I owe my life to the LDS.” On the way to the office in Poughkeepsie, Boris wonders if he too owes his life to the Mormons.

The next morning Boris is glad to be doing his missionary training in another town on the other side of the mountain, far from any of the laid-back townspeople who had once respected him. Today he is alone with Gregg and the plan is to simply walk around and let it be known that they are more than happy to lend a hand if anyone in the community needs one. Boris gulped down a caffeinated iced coffee at Dunkin’ Donuts while Gregg was in the men’s room. Boris is not yet convinced that there is a God up there really concerned about whether or not humans drink beer or coffee or Diet Coke. This much he buys from Marina’s thinking. But hasn’t Doug come through with plenty of leads for Marina’s private business? Marina now doesn’t have enough free time in the day to teach piano to all the Mormon children on her client list. She is no longer protesting Boris’s involvement with the Latter-Day Saints.

“As long as you keep our Sasha out of this. Spasiba! No Joseph Smith talk for little Sasha, okay?”

He and Gregg stand on the grass in front of an Orthodox Jewish synagogue.

“A lot of observant Jewish people live in this neck of the woods.” Gregg smiles. “Don’t say so much around here. Let God speak the truth himself.”

Things are getting better back home. At night, Marina is biting him again, even more than the Ulster County mosquitoes are. Doug is nearly finished renovating the first floor of his magnificent house for them to move in.

Boris observes an older balding man dressed formally and wearing a yarmulke coming toward them on the sidewalk. The man flashes him a knowing smile as he passes toward his parked station wagon just across the street. Boris feels awkward. He has to say something to justify his presence in this man’s path.

“Good day, good day, fine sir.”

The man stops in the small side street facing the synagogue and turns around.

“Where are you from? You have a Slavic accent.”

“Minsk. I from Minsk. You no know it.”

The Jewish man scratches his beard.

“I certainly do know it. My parents were from there. My grandparents got shot cold in the head outside of Minsk during the transports. Luckily, I was born here.”

Boris doesn’t know what to say. He doesn’t qualify in any way as a Jew to these people, as it was his father, not his mother, who had some Jewish blood. The man with the yarmulke is staring him up and down like he is a long-lost relative, a relic from another time, a representative of all that meant Minsk. He looks over at Gregg, a basketball player clearly in the wrong uniform, still wearing a pleasant expression. Boris tries to flash his best smile, but his lips refuse to part. He is at a loss for words.

“You should visit the Minsk. It has been change a lot,” Boris says finally.

With this awkward comment already stupidly released into the air, Boris turns quickly and with Gregg following, stumbles away up the sidewalk, tucking his Mormon tie into his pants.

Back in Gregg’s SUV, they ride silently through glorious mountain passes. Boris sees a family of deer grazing in a field off the highway.

Gregg glances over at him. “You had a tough morning. It gets easier. Let me treat you for brunch—or if you want to wait, Ronda’s has a great early bird.”

Early bird? Once Gregg makes clear the meaning, that he isn’t talking about shooting a bird early in the day, Boris is exuberant about the expression and jots it down in his notebook. Yet he is too hungry to wait for this early bird to come. They stop at a roadside diner right next to a vacant commercial property. Someone has spray painted across the white shingles of the empty building, JESUS LOVES US ALL EVERY MINUTE OF THE DAY.

Gregg shakes his head as he gets out of the car and slams the door. “That’s not our idea of Jesus Christ. We don’t write things like that, you know what I’m saying?”

“Okay, no good that way.” Boris shakes his head at the same speed that tall Gregg is shaking his. The truth is that to Boris, Jesus is Jesus, and with the exception of the stupid icons and superstitious nature of the Orthodox, he can’t really see all the distinctions between this denomination and that one. Americans live for these distinctions. Boris marvels at the wonder of American individualism as Gregg orders his meal at the counter.

“Yes,” Gregg looks up at the waiting waitress, “can I have an order of dry wheat toast, just lightly toasted, with soy butter on the side and a lightly fried poached egg on a separate plate. Thank you, ma’am.”

This is America. Everything custom to your liking. Individualism. He has trouble pronouncing the word in his head. The way he says it, broken up, individualism is composed of eight syllables. In Druzba, you say you want an egg, and you get an egg. Zayitchka, egg, nothing more. In fact, you are lucky if you even get that.

He tries ordering breakfast like an individualist.

“I like two egg, maybe three cooked, but not so, you know, toast yes, but not so much with butter, potatoes yes, but cook them nice, and not exactly so mush and . . .”

Gregg interrupts. “Boris! Why don’t you just order the number four?”

Boris suspects that Gregg is ashamed of him.

They make their way through one more town, and are even able to give away a few Books of Mormon. One elderly woman with a stutter asks Boris a lot of questions about Mormonism, and Boris is delighted to come upon someone with enthusiastic ears, or at least with a desire for companionship.

Boris practices what he has learned at the Missionary Training Center, his arms extended as he speaks, half-believing his words about the great Joseph Smith.

“He was the Great Jehovah of the Old Testament, the Messiah of the New. Under direction of Father of His, He was Creator of Earth.” Boris stalls his monologue for a moment and looks down at the frail old woman who is sitting on the bench. She seems to be listening. It is hard to tell.

“And, uh . . . oh yeah, all things was made by his, and without him was not anything that was made that was made. That was from John 1:3.”

The reddish-yellow sun is curling down over the peaks of the Catskills as Gregg turns onto Boris’s dead-end street. From the passenger’s seat, Boris sees Marina and Sasha waving from the porch as the beat-up white house comes into view. Sasha has on a white New York Yankees T-shirt, and with the last of the day’s light upon him, Boris can see the outline of his son’s inverted rib cage through the shirt. It makes Boris twinge, a great void in his son’s midsection, something out of a National Geographic magazine pictorial on famine in Central Africa. He reminds himself that he has Google evidence that Sasha’s condition, his pectus excavatum, is completely harmless. The operation would be purely cosmetic. In Belarus the kids laughed openly at Sasha’s deformity; even the teachers made comments. Some of the old babushka types held tight to their medieval beliefs that such a deformity could only be the work of the devil. American individualism has saved Sasha from all this. No one seems to comment or care that his pectus doesn’t look like the other kids’ pectuses.

Boris waves back to his family as Gregg pulls in. He notices Sage smoking what seems to be some kind of illegal substance on the roof and he is immediately embarrassed by his black book and uncool dress.

Later, after Gregg has left and Sasha has fallen asleep, Sage comes downstairs with her giant collie poodle Che, for a glass of pink lemonade. Marina is inside cleaning her piano keyboard. Sage speaks.

“I saw you ’round the last few days all dressed up.”

Boris doesn’t know what to say. He has nowhere to hide. Sage smells of what she has been smoking, pungent and woody.

“Hey man.” Sage picks fleas out of Che’s auburn hair as she speaks, “Whatever gets you through the night is all right. You know what I mean?”

Boris pours her another glass of the pink beverage from the pitcher resting on the table.

“Thank you, Sage. Thank you.”

They sit in silence together beneath the Smirnoff umbrella, sipping lemonade. Boris thinks to himself that Sage, unlike many of the other townspeople he knows, genuinely embodies the spirit of “live and let live.”

July 4th (just over a week later)

Boris sits hiding in the back of the local Dunkin’ Donuts sipping a fully caffeinated large house blend. Today is going to be his first 4th of July spectacular barbecue, and it will take place on the big lawn his family now shares with Doug’s. There is a lot to celebrate, yet Boris does not feel right inside. Elder Timothy overheard him on a few occasions chanting Guided by Voices songs, and chastised him for this in a closed-door discussion in his office at the missionary center.

“You cannot be representing the LDS and voicing such crude words. I did my research on this music group. There is cussing. There are gothic undertones. At the risk of sounding old fashioned, this stuff is the work of the devil. Mormons cannot live a double life. Elder Doug tells me you drink caffeinated beverages regularly. Is this true?”

Boris looks around the store to make sure none of the elders are around. An obese teenage girl is ordering four jelly doughnuts. He takes a big sip of his coffee. He likes the taste and looks forward to the daily morning buzz. Timothy has made it clear that his apprenticeship days are coming to an end, that he has reached a crossroads and will soon have to make a lifetime choice. There is a band playing on Main Street and Boris sees the outline of a row of confident American flags in the reflection of the window. Boris tries to imagine a life without coffee or Diet Coke, without Guided by Voices songs on his iPod lifting him through his days, and without sending and receiving illicit tweets to and from Didem in Brighton Beach. He considers that Doug’s great-grandfather had three wives back in the day, but polygamy is unfortunately no longer part of the Mormon deal, at least not in New York. No, there is no choice. If he wants to join the elders, he will have to give up all of these earthly pleasures.

Boris orders another large house blend and returns to his seat. Marina will be expecting him soon, back from the supermarket with the makings for a Russian potato salad for the festivities.

He turns up one of his all-time favorite GBV songs, “Hope Not,” on his iPod.

He whispers the words along with the singer:

There’s so many things people say

Just to help give it away (but get in the way)

I won’t try to figure things out

It’s complicated so when doubt

I start crying

Attracted to the light

Everything will be all right

Attracted to the light

Everything will be all right

He shared this song with Linda, his host mother, in her darkest moment, and it had cheered her up a bit.

Boris hums Linda’s favorite verse from the GBV song. He leaves Dunkin’ Donuts and the Linda clip behind and starts up Main Street hill, past the mostly closed stores, toward his first all-American celebration.

July 19th (two weeks later)

Gravel Head Park is packed. It is Sunday and super hot and humid. They have the fancy water sprinklers on and Sasha is playing with some of his new friends. Boris contemplates his surroundings. Everyone is happy, animated, and speaking to everyone else. No one is complaining about everything like they do in Druzba, and most importantly, no one seems to notice his son’s irregular pectus.

Boris looks up and sees Doug’s three daughters waving at him from the swings. There is Doug, right beside them, helping a grandmother dislodge her grandson’s legs from the baby swing. Boris notices that Doug never seems to take off his white-collared shirts; always on duty he is. Boris wonders if he can ever be as disciplined in his devotion as Elder Doug. When will he know for sure, without a doubt, that he believes in God, that he is a true Mormon? Will there be a signal from the sky, or at the least a clear signal in his head? For Boris, the idea of being religious means being able to believe in miracles. It means being able to find your way through all the clouds of skepticism around you.

Boris had experienced a miracle of sorts this past Wednesday when he received a Gmail from California. He had been at his favorite table in the back of Dunkin’ Donuts when his iPhone beeped with the message, You have received a message from Linda. Boris nearly spilled his mountain roast.

Dear Boris,

Sorry it has been sooooo long. How are you and Marina doing up there? How is Sasha adjusting? I hope everything worked out ok with Sage. I felt awful about abandoning my lovely Belarusian guest family.

I came back to live with my father in Sacramento. Now Glenn is here with me and we are going to try and start over. We still want to start a family.

So many things have happened I wouldn’t know where to start.

Boris, I know you and understand it is in your nature to reject the offer I am about to make . . . but please don’t. I want to pay for Sasha’s surgery. Glenn has a new business and things are looking very positive for us. I know how hard it is for you and Marina to live with your son’s condition. It is the least I could do.

I will send you our new address and you can send me the bill.

More soon.

Love,

Linda

Boris’s tears had made his apple cruller soggy.

Perhaps this is the miracle Boris has been waiting for, a sign from God. Linda, out of genuine human goodness, has agreed to pay the big dollars needed to make right Sasha’s inverted pectus. What greater miracle could Boris experience in his life? Boris takes this as a sign of the Lord’s working. How can he not? Another sign is the change he sees in Marina. Marina has gotten closer with Sara, Doug’s wife, now that they share a Victorian home. Boris was surprised a few days earlier coming back from work to see Marina and Sara on the porch paging through the Good Book. His Marina holding the Book of Mormon!

Boris checks the time on his 3G iPhone. Every Sunday at exactly 2:30 p.m., Boris is expected to take out a calling card from his wallet of fine Turkish leather and call his mother in Minsk. It is almost bedtime across the Atlantic and Baltic. He pictures his mother lying on the worn-out red sofa waiting for the phone to ring.

“Boruchka, everybody healthy and eating well?”

Every week the same question begins his conversation with his mother, word for word, verbatim. Boris would be concerned if those were not the first words coming through the receiver.

“Everything is fine here. Beautiful. Have you heard from Yuri?”

An ice cream truck has pulled up alongside the park and Sasha is looking over at him and pointing at it.

“Yuri?” There is a long silence.

“Mom?”

Boris’s head flashes with imagery: a Romanian prison . . . a barrage of Bulgarian Mafia bullets fired from Kalashnikovs.

“I have not heard from him in a long time. On Thursday I received a large shipment from him, but with no return address.”

Boris hands Sasha a towel and two singles. His son has developed an affection for Toasted Almond.

“What kind of shipment, Mom?” Boris’s ears stand at full attention. He has not sent his mother any packages since Easter.

“Dunlop rackets.”

“Sorry, Mom. The connection is breaking up. Dunlop?”

“Yes, many boxes. Maybe one hundred tennis rackets. It’s crazy, I know.”

Boris watches Sasha waiting patiently on line for his stick of ice cream. He likes that his son has turned out to be such a laid-back boy.

“Was there a note? Did Yuri leave a note?”

“Yes, very short. Just two words. Resell them.”

Boris sits in the park the rest of the day, not moving from his spotless green bench. Sasha can play with his sand toys without break until the sun goes down. Boris has his iPod on and he is trying to be a good Mormon. He is making an effort to keep his fingers off the GBV tracks. He has some “smooth jazz” on instead and it isn’t all that bad. It was Yuri who had introduced him to the music of Guided by Voices back in Druzba. Boris had always been the computer geek, out of touch with the Minsk youth culture. Yuri, drawn to the urban scene yet always marching to his own beat, had connected with the gothic angst of GBV. One day he came home drunk and handed Boris a Maxell cassette.

“Life is hard, but these songs are so pretty. Listen.”

Where his younger brother is now, who knows?

Boris spots one of the hippie mothers who closed the gate on him when he made the stupid effort to proselytize in the playground. She is smiling at him now from the jungle gym; why, he does not know. Perhaps she does not recognize his face. His beeping iPhone interrupts the mysteriousness of the moment. It is one of his clients. He has to pick up.

“Hello? Yes, Mr. Caldwell! You fill out application and send it me . . . What’s that? No problem, I work every day. Boris work Sunday, Saturday, don’t matter.”

Elder Gregg had connected him with a business job working for a foreclosure rescue loan company just outside of Kingston. It is a hundred-percent Mormon-run business.

“Okay. Okay. No problem. You bring it me tomorrow. Bye bye.”

Boris grins. He has a top cell phone. He has a list of clients. He has become an American businessman. In fact, his phone has been ringing with new clients all week long. The banks can’t save people’s homes, but Kingston Loan Dog can. Elder Gregg had been reluctant to vouch for him because of his limited English, but Boris reassured Gregg that he will stop by the MTC every day on his way home from the office for an intensive language training session.

John Dorsey had started Twitter from nothing. He, Boris Mosheyev, will save some money, earn his Twitter accessory copyright soon enough, and be on his way.

Boris checks the time. It is half past one, and Marina will be expecting Sasha home soon for his Sunday lunch of borscht and Ukrainian rye.

Boris gets up from the bench and walks toward the crowded sandbox.

“Sasho, Mommy will waiting. Let not forget your pail.”

Marina speaks to their son only in Belarusian. Boris speaks to Sasha solely in English. Their son will grow up perfectly bilingual, an American success story. Boris takes Sasha’s sandy soft palm in his hand and waves one last time to Doug and his daughters. Sasha waves to his friends with his free hand.

Boris imagines his son’s future. Sasha, his given name being Alexander, can have his family name Mosheyev shortened, and will then be known as Alex Moses. Boris likes the sound of it. It sounds like the name of an NBA star.

Boris closes the gate to Gravel Hill Park and with Sasha’s fragile little fingers wrapped around his, continues straight up the hill toward their lovely Victorian. Alex Moses, why not? After all, this is the country of reinvention. Alex will soon lose all memory of his bleak Minsk childhood.

They turn the corner of their peaceful side street. Boris loves the wild western sound of his street’s name, and his heart jumps each time he passes the nicely constructed green street sign: BEAVER WAY. Boris can smell the sour cream and beets waiting for them in the kitchen. He lets go of Sasha’s hand and lets him run the last half-block. Boris watches in awe as his son’s strong legs take flight. Alex Moses, a Mormon of Slavic heritage, will grow up with a perfect pectus in the comfort of Upstate New York America.

Copyright © 2011 by David Rothman.