Upstate, it takes a very particular kind of bond to make us unafraid to whisper about who we are, and all the things we’ve done.

My mother is afraid of New York City, so when we really need to see each other, I take a long northbound train into a dank pocket of Earth known as the “armpit of Upstate.” I want to tell her that, with all the Confederate flags and rubber testicles dangling from pick-up trucks up there, it is I who should be afraid to visit her. But I never do. Besides, she’s not afraid of the city because she thinks it’s dangerous; she’s terrified the grizzled Manhattan streets that once lined her youth might remember her, and whisper to the trees about the things she’s done.

I always try to explain that New York City is enormous and nobody would ever recognize her after all this time, but she knows better.

So, I visit her up in the valley, where she likes to take me walking around Walmart. “Sam Walton is an evil man,” she reminds me, “but you won’t find better bargains than Walmart has.” I push the cart beside her, pausing every so often to let her fill it with new toothbrushes and candles, strolling up and down aisles full of people who know about us, and all the things we’ve done.

We didn’t grow up wealthy, that’s for sure. But we weren’t the poorest family on the block either. We were the second poorest. We couldn’t afford TV or Fruit Roll-Ups or to be in sports, but the Mills family couldn’t even afford winter jackets. They lived up Division Street from us, and each year I’d watch the Upstate seasons weather the Mills family—their too-small hand-me-downs bleeding cotton with busted zippers. I always knew when they were leaving for school in the morning because Mrs. Mills would holler “ALL ABOARD!” as the kids piled inside their big frozen minivan.

Mrs. Mills was the first obese woman I’d ever seen, and it was hard not to stare. She had this fatty pouch of blubber that hung between her legs, which I thought was her vagina. I wondered if that was the natural evolution of vaginas for some women, and if mine would maybe look like that someday. She had six kids, all thin as rails. I used to imagine that, instead of blankets, the kids slept under their mother’s belly like newborn chicks scrabbling for warmth. My brother assured me that was ridiculous, but that it was likely that Mrs. Mills got so hungry one night that she ate her husband and that’s why the kids didn’t have a dad.

Anyway, it’s not like our winter wardrobes weren’t hand-me-downs too, but my mother had the good hookup to our town’s wealthiest families with kids. Any rich kid within twenty-five miles who outgrew a pair of Nikes or got a Christmas sweater they didn’t like would soon be visited by my mama, ready to stuff their unwanted goods into a sack to bring home for us kids to model in front of the bathroom mirror. Occasionally there wouldn’t be anything worth salvaging, but for the most part you could hardly tell the clothes were used. Either way, whenever Ma dropped a bag in front of us she’d say, “Now remember: you don’t have to tell anybody where these came from, and you look stunning in them anyway.”

One winter afternoon in the fourth grade, Ma brought me home a red knit sweater from Abercrombie & Fitch—by far the most luxurious item ever to hang in my closet. It had pockets, a hood that zipped, and most importantly it bore the AF insignia in shiny gold thread. And it was brand-new, tags attached and everything. Somebody had paid $59.98 for it, so I clipped the tag and saved it in my dresser drawer to use as Barbie currency.

And the sweater could not have come at a better time, because the next day was “dress-down day.” Every other day of the year, we girls wore blue-and-white plaid jumpers over white blouses; but dress-down day was our chance to show everybody how we got down on the weekends.

That night I breathlessly put together my ensemble for school, pairing my new red sweater with khaki pants and penny-loafers. I lay awake all night fantasizing about strutting into school with my fancy new sweater, explaining to everybody that we’ve actually had money this whole time, it’s just a sin to flaunt it.

The next morning in homeroom, I could tell everybody noticed how fly I looked.

“Is that from Abercrombie and Fitch?” Chelsea asked suspiciously.

“Hmm? Oh, this? Yeah, it’s like my favorite store. Do you ever shop there?”

The other girls gathered around.

“Uh, yeah, of course I do,” Chelsea replied. “I have at least like . . . a hundred things from Abercrombie. My mom takes me shopping there all the time.”

“Yeah, mine too,” we all said.

It’s not like I was unpopular. As a class clown with access to her dad’s porn magazines, I got plenty of attention for things like blowing milk bubbles out my nose or drawing anatomically accurate dicks in my notebook. But it was seldom that I was a part of regular old girl-chat, and it was intoxicating.

I was just about to show everybody how the sweater’s hood could zip open into two pieces that draped over my shoulders when Chanel Diamond rolled in like a bad dream.

“Hey”—she pointed at me—“that’s my sweater!”

My eyes fell and I wrapped my arms around my chest. “No, it’s not. This is my sweater. I got it from Abercrombie and Fitch.”

“No, you didn’t. My dad got it for me at the mall and I hate that color so my mom donated it to your mom at Church. In fact, I’m pretty sure those pants used to be mine too. Are they from the Gap?”

Even if she hadn’t been in a caste above me, it wasn’t hard to believe Chanel’s accusations. She was tall and thin, and I had more of a meatball physique, so my whole outfit was empirically too long and too tight. Chelsea grabbed hold of my sweater and lifted it to reveal the label on the back of my pants, shouting, “Look, Chanel, they are from the Gap. See? You were right!”

Chelsea was technically my friend, but she never ever missed an opportunity to climb. Chanel laughed, and then everybody laughed. Everybody except Crystal-Lynn Mills.

The Mills kids were always in trouble at school for skipping gym class or forgetting the words to the Act of Contrition. Crystal-Lynn wasn’t supposed to be in my class, but she got held back after the bus driver stopped giving her rides to school because she smelled like wet cigarettes and pee. That’s not what he said—that’s just what we all assumed.

Crystal-Lynn’s hair was mostly clumps, like mine, but blonde and full of lice. Every so often, when my hair got really bad, our teacher, Mrs. Frank, would call me up to her desk.

“I just can’t look at this anymore, Sarah,” she’d say, working her fingers through my snarls. “If no one’s going to take care of this, I guess I will.” Even though the other kids looked on in wicked delight, stroking their French braids and passing notes, when Mrs. Frank played with my hair I was at peace.

But Crystal-Lynn had head lice (or at least that was the rumor), so when she was done brushing my hair Mrs. Frank did her best to avoid Crystal-Lynn’s glances, lest she ask for a turn.

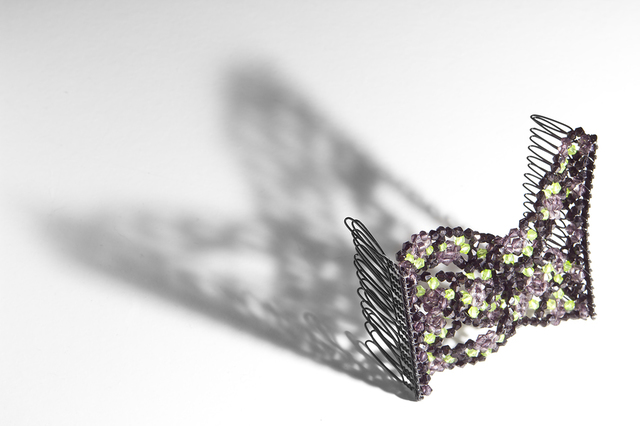

One time, Mrs. Frank styled these twists on top of my head, fastening them with a variety of little clips. She used a pink piglet clip, a yellow duck, a green frog, a couple that were plain white, and one butterfly clip whose kaleidoscopic wings opened to reveal eight little teeth that actually sank into my scalp. “There,” she said when she finished, “spiffed you right up!”

The afternoon I was outed as a known recipient of Chanel Diamond’s throwaway clothes was a devastating blow to my social status—namely, my seat at the lunch table. Usually, I sat between Jordyn and Kara—a position granted to me for my excellence in dodgeball, and for teaching the other girls how to masturbate under a bathtub faucet. But on that fateful dress-down day, into the second bite of my taco, I felt a tap on the shoulder. It was Chanel.

“Sorry, Sarah, but Morgan is sitting there today. Maybe you can sit over there with your friend Crystal-Lynn.”

Chanel laughed, then everybody laughed. I considered telling her that Morgan could have my seat when she pried it from my cold, dead fingers . . . but I knew resistance against this many girls would be useless. So, I took a long swig from my carton of two-percent, stiffened my upper lip, and surrendered the seat to Morgan.

Crystal-Lynn always sat alone, so when she saw me approaching she sat up straight and began smoothing out the wrinkles in her jumper.

“Hi, Sarah!” she said before I sat down. “Want some of my taco?”

“No, that’s okay, I’m still working on mine.”

We sat quietly for a minute, mooshing our sporks into stray beans, but I could tell she was thrilled to have a lunch date. She hit me with all kinds of questions about my favorite color, my favorite Spice Girl, my favorite name for a pet. Before I knew it, the shame I’d felt for being cast out from the cool table had gone. I told her all about the stray cat I’d adopted, and how he wouldn’t let anyone hold him but me. We talked about the bus driver and how it smells like farts on that stupid bus anyway. We talked about school, and how much we hated when kids called their moms crazy. We talked all day.

A couple days later, Mrs. Frank handed me a stack of homework to give to Crystal-Lynn, who would be out of school for a few days. She told me she was bequeathing this responsibility to me because she knew we were neighbors, but I got the sense that she had heard about our bonding at the lunch table. I hoped Mrs. Frank wouldn’t hold that against me, or stop doing my hair. Regardless, I told her she could count on me to deliver the work.

I’d never actually been to Crystal-Lynn’s place, but I knew which one it was. Though Mom made fun of it, I thought the Mills’ decision to put a couch on their porch was genius.

When I arrived, the front door was ajar, so I slipped inside. I found Crystal-Lynn in the living room, alone, watching Ren & Stimpy. I cleared my throat. “Hey, Crystal . . . I brought you your homework. Are you sick?”

“Sarah!” She leapt off the couch, thrilled and not at all startled. “Come see my room!”

She took off down the trail of beer cans and Big Mac wrappers that passed for a hallway. Her bedroom was surprisingly clean. Only a bit of the detritus had filtered in.

“Don’t mind all the shit,” she said, kicking an empty Campbell’s Tomato Soup can out the door.

I couldn’t believe my ears. Though I’d heard my Mom do it a million times, I had never actually uttered a swear word myself. I took a breath.

“Yeah, there’s a lot of shit at my house too,” I said.

We smiled at each other and settled into her bedroom.

“It’s cool you get to be here by yourself,” I said, perusing her collection of coloring books. “What time do your parents get home?”

“Well, my brothers will be here later and my mom will . . . also come later.” She blinked. “My mom is a nurse.”

She seemed a little nervous, so I told her about the time an off-duty nurse at Price Chopper plucked dozens of cactus spines out of my palms after my mom left me alone in the plant aisle. I told her she was lucky to live with a nurse. She rolled her eyes.

“So what about your dad?” I asked, doing my best to pretend I didn’t know he was gone. “What does he do?”

She snatched her homework out of my arms and stacked it on a chair.

“He doesn’t do anything,” she said.

I plucked a Hot Wheels coloring book from the shelf and thumbed through the pages, but everything had been colored already. I felt a quick lurch inside. I wanted to leave.

“Hey, I got an idea,” Crystal-Lynn said. “We can play barbershop like in Mrs. Frank’s class. I’ll brush yours first.”

Her hands reached for my head. I stiffly recoiled.

“No thanks. I actually have to go home now.” I tossed the coloring book onto the floor and watched the tender excitement in her face bleed into a grave awareness of self.

Her expression made me think of my mom when she’d remind me and my brother that we didn’t need to tell anyone where our clothes came from. I’d always assumed she told us that to compensate for her own insecurities about being poor. But as I watched Crystal-Lynn sort through her Language Arts booklet, eyes full of tears, I realized that what she meant was: we don’t owe anybody an explanation. That it’s more important to be proud of who you are than to be worried about who everyone else thinks you are.

“Okay, well, bye, Sarah,” Crystal-Lynn said. “Thanks for the homework.”

“Wait a minute,” I said, searching. “Try this.” I yanked the butterfly clip Mrs. Frank gave me from my hair and presented it to Crystal-Lynn. She held it delicately in her hands, cupping them slightly as if it might fly away. She opened its wings and stuck it to the top of her head.

“There,” I said, “spiffed you right up.”

Two weeks later, Crystal-Lynn was pulled out of school. That was the last time I saw her.

Until, that is, a few months ago when I made the trip upstate to visit my mom. This time Mom had me meet her at Walmart so we could get sandwich fixings before the deli closed.

I was greeted at the entrance by a very pregnant woman with a blue vest adorned in Sam’s Choice pins, and a head covered in variegated butterfly clips.

“Welcome to Walmart, Sarah!” she said.

“Hey, Crystal-Lynn. How have you been?”

And we went strolling up and down the fluorescent aisles, whispering about who we are, and all the things we’ve done.

Copyright © 2018 by Sarah Riccio.