After losing everything you love, how much more would you give up to remain in the happiest place on earth?

Gerald Chimes, childless at forty, is a permanent guest of the confected world. He enjoys the liberty of the Kingdom, comes and goes as he pleases in every Park. Everyone understands; everyone remembers: the Staff in uniform and at attention, the Characters in costumes authentic down to the button, to the thread that holds the button in place. Even if they weren’t there, it’s as if they were. What happened to Gerald no one can forget. Management briefs new hires, who take the awful story to their hearts as a thing they have always known.

The Parks open at eight. Gerald wakes at six, showers, shaves, stands in his closet and picks out his clothes. White linen trousers and tangerine silk? Pleated cotton khakis and cerise cotton tee? Never a tie, this being June and Florida, the godforsaken heart of it miles west of the ocean, miles east of the Gulf. No breeze to speak of, not a whisper, not a breath, as if MM Entertainment arranges prevailing winds for Gerald’s solace, in the service of which no notion is excessive, no effort too great. Re-engineering the microclimate of Kissimmee and vicinity should be impossible. But Gerald, having seen them work, would not be surprised.

He slips chinos from a hanger, pulls a polo from a drawer. The pants have an opalescent sheen that seems liquid in the streaming light. The shirt is purple, as ripe as a plum. Gerald watches MMTV as he dresses, notes the Special Events on tap at each Park, live music and pyrotechnic displays (the latter still permitted only on his say-so), the slate of Character Breakfasts, Lunches, and Dinners held daily for the amusement of children. Seating times he ignores; all restaurants welcome him at all hours of the sixteen-hour day that ends sharply at midnight. Gerald needs no reservations and so he makes none, and so he has none. A table is set for him, his table, cloth of red silk at Hibachi House, royal blue linen embroidered with white fleurs-de-lis at the bistro, red-white checkerboard at the trattoria on the pavilion that is Italy’s claim to fame. Pinot Grigio chills in an ice bucket. If the chef prepares duck or venison, mutton or quail, the Cabernet, the Shiraz, the Pinot Noir, uncorked hours beforehand, breathes. Does Gerald desire a platter of carpaccio, fondue of bagna cauda, oysters on the half-shell, bowl of bouillabaisse, cup of lobster bisque? He only has to ask. Gerald eats like a king, he drinks like a lord. Ordinary guests, spying his plate, ask le garçon to bring “what that guy is having,” dining alone.

Ah, oui? Monsieur’s entrée is the last of its kind, his appetizer a delicacy rarely available. Alors, we shall not see des escargots for quite some time. During your next visit, perhaps, you will with luck find us more favorably supplied. Until then there is cheeseburger.

But but says the guest. Tut tut says the waiter and disappears. At Gerald’s table napoleons arrive on Sèvres, espresso in Limoges. At meal’s end he presents the minted ingot, bas-relief talisman of 10-karat gold inscribed with trademarked devices, that identifies him as a permanent guest.

Dressed and fresh, happy face in place to meet the day, Gerald elevators from his permanent suite to the hardwood lobby of the Boardwalk Hotel. Front Desk Specialists, no fewer than ten, smile and nod, their eyes slanting past him. Bellboys touch brimless caps, perform shallow bows. The Bell Captain gazes at Gerald and lays a hand over his heart. Only the chambermaids turn away. Why won’t they greet him? They are mostly slim, unspeaking women, mostly from foreign lands. What has Gerald done that they disapprove? He himself is innocent, he has harmed no one. Perhaps these women, working long hours, sending money home, are not aware of his pain. Second-degree burns over half his body have been the least of it. No doubt they cannot guess how MM Enterprises taxes every resource to make Gerald whole—that, in lieu of litigating the lawsuit Gerald still can bring and would be certain to win.

Gross negligence. Wrongful death.

These words cross the inner sky of Gerald’s mind, shedding a shower of sparks. He does not ponder them, despite lawyers' advice, and when he pushes through the double doors and steps onto the teak veranda, word-conjured hauntings effervesce in the golden air.

Craving croissants and café au lait, Gerald walks to France. A smile brightens his face, and why not? The day is fine, his health is good, his clothes are simple and exquisite. He totes no wallet, cell phone or briefcase, just the key card to his permanent suite and his minted ingot, the two-ounce golden rectangle that vouchsafes him entry everywhere. Unlike tourists, he carries no camera. What would he photograph, when he is always here? Also, it is part of his concord: no cameras. Gerald cannot blame them. Without a camera his current privileges would have been harder to achieve. MM Legal sat up and took notice when it watched the video of Gerald’s loss. Suits murmured darkly, sickly looked sideways, shook their heads. Then they offered a deal.

Perpetual service for life, preferred interment beneath the Castle keep when he dies, and in return Gerald Chimes tells no one. He will never speak of it in interviews, never write of it in books or on blogs, never mention it in articles, essays, columns or letters; not on websites or bulletin boards, billboards or Post-Its, flyers or pamphlets, anywhere. At all times in all forms, what Gerald knows and saw and in terror lived through remains a tale untold, and a private pain. The video itself Gerald cannot so much as allude to. The concord he’s signed stipulates his silence, MM Legal covering the contingencies a damn sight better, Gerald reflects, than the Entertainment division did the night of the Accident.

Ascending a path of interlocking bricks seamless beneath his feet, Gerald approaches France. It lies to his right, beyond a stone bridge that spans a river wrought by bulldozer and backhoe. Here, this river is the Seine and bears a steady traffic of bateaux mouches ferrying tourists among the Parks. Generally, Gerald avoids les bateaux. They run diesels, for one thing, and walking alone is safer. Management might hire spies, after all, and in an unguarded moment Gerald might let a detail slip. He does not yearn to spill his heart. He wants to speak of it as little as Management requires him to speak of it, which is not at all. Still, conversation is dangerous. It is friendly folk he fears. The Parks are full of them: motherly types with apple cheeks and pumpkin breasts leading hearty husbands by the chin, worn-down northerners squinting against the light.

Are you here on your own, then?

One of them, one day, is sure to ask—and what will Gerald tell her? He can lie, of course, he can try to; it is after all the essence of his deal. That he wear the clothes, eat the food, see the sights and be seen himself as happy and calm and full of cheer, a smile on his smooth-shaven face. They have asked him to be agreeable, approachable on informal footing, to trade pleasantries with tourists, proffer advice about beating crowds, avoiding lines, capturing Fast Passes for popular rides. It frightens him. How many words separate casual banter from the words he must never say? The pointed question, the gentle probe.

Aren’t your children jealous of your being here without them?

It could happen so easily, from nothing more wonderful than his impulse to reply to kindness with trust.

My children aren’t—

They didn’t—

They can’t—

Answering one question, he would answer them all.

Lightly perspired, Gerald Chimes arrives in France. Il a arrivé, he imagines them whispering, mouths behind hands, les garçons and belle filles and insouciant jeune gens. Et il va rester. Nestled beside the Seine, a café offers a welcoming bustle. Its awnings are unfurled, its coffee is dark, its cloths, just laundered, are whitely laid. Gerald takes a seat. Le garçon appears briskly and from a negligently balanced tray serves café au lait and twin croissants, the latter exuding from their fine-grained goldenness such aromatic warmth that Gerald, for the first time in two years, has a thought he recognizes as sexual. When he bites into the flaky shell, it exfoliates with a taste of butter and baked-in heat. Gerald sips coffee, nibbles the confection, watches the Cathedral’s stained glass flare in the sun. Despite being just one-third scale, the replica is convincing and Gerald, who has never been to Paris and knows he will never go, feels something like peace cover him. The stained glass is real, that is, imported from Troyes in straw-filled crates and installed here by French glaziers using tools brought from home. Panes illumine as the sun surmounts a turret of the Chateau d’If, set in conspicuous isolation on an island in the Great Lagoon. The turret’s height, the angle of the morning sun, the Cathedral’s magnificent window: their convergence seems to manifest what MM World calls magic. Gerald knows better. Calculations have been made, cornerstones precisely placed. Everything in MM World that appears magical is a product of planning.

Gerald eats the second croissant. Overhead, the great rose window glows vermilion, purple, emerald, gold.

Every day of his life can be like this day. Until he dies, Gerald Chimes may idle away his hours in France, in China, in Canada or Japan, in Italy, Morocco, Germany, and Spain. He can spend the day, walk the loop, make the Grand Tour in an hour as the wealthy of a distant century made it in a year. The Kingdom he can visit at night, when the crowds have dispersed and the children, most of them, are locked away in Resort bedrooms, safely asleep.

Gerald himself sleeps when he wishes. He has no place to go, no person to visit, no obligation to meet.

England. Norway. Mexico. Greece.

He shifts his chair to face the Chateau. The sun, having cleared its tower cell, laves his face with kisses.

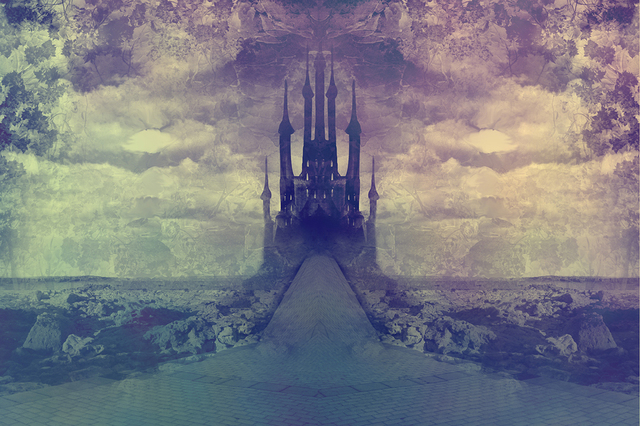

Façades freshly painted and plate glass shining, the Kingdom is resplendent in early summer sun. At the upper end of Main Street, a fairytale Castle rises from a man-made plateau and towers into an azure sky. Strolling toward the Castle, Gerald Chimes surveys the tourists and understands his plight. The women here are moms with kids. Definitely not what Gerald has in mind; definitely not what he, two years removed from soul-deep loss, is looking for.

Perhaps Management can offer guidance. Or, no—the Entertainment division. Isn’t that its role? To make people happy? Gerald ponders possibilities. There are the Staff of each Resort, the Attendants of each Park, also waitresses and shop girls and concession workers and ticket-takers and chambermaids—no, not chambermaids. There are the Princesses. Most especially, the Princesses. More than a dozen by now, which in real terms might mean fifty or sixty individual girls. Snow White. Cinderella. Ariel. Aurora, Princess of the Dawn. Mulan, a Japanese warrior. Very good. Pocahontas. Esmeralda, gypsy girl of occult origins. Jasmine, a sultan’s daughter. Belle, who is French, who lives in a village in France. Loves books, has a voice like an angel. Whose name means beautiful.

Tourists mass on Main Street, surge in waves. In the distance the Castle looms, its intermixed blue-white, amber-white blocks giving its surface a soapstone gleam. Do they hide inside it, Gerald wonders, and then, arrayed in petticoat and gown, a deerskin wrap, simple skirt of contadina, the gauzy veils of Eastern wont, suddenly appear as if from nowhere, as if by magic? MM World prides itself on the reality of its illusions. In its Kingdom fantastic tales are real, legendary Characters walk the steam-cleaned streets. It wouldn’t do for Gerald to mash Snow White with an invite for drinks. He cannot sidle up to Jasmine and pinch an inch of robust derrière. No no no. Think of the kiddies, their scandalized moms and smirking pops, paying customers all. Aladdin only may be familiar with that one, a raven-haired beauty of an antique land, and then in public only so far as a kiss.

Still, it seems not impossible that one of these women would not dislike an evening in Gerald’s company. They spend their shifts posing for photographs and signing autograph books for little girls who do not understand that they are not real. That they are playing a part, wearing the costume and speaking the lines, and after hours having a private life more or less like anyone else. Which is how Gerald wants to know them, one of them, and the only way Management would allow it.

Tourists pose with the Castle as backdrop, hug each other laughing or weeping with joy. Gerald veers right, descends the path that skirts the Castle, eyes peeled for Aurora in a portico, Belle on a balcony. No luck. Perhaps it is too late. The sun is sinking, the day is on the wane. Soon flood lamps will illuminate the Castle in the classic way he remembers from the old television show, on Sunday evenings when he was a boy. The Wonderful World. Yes, it was. Before he learned by losing it that only his family loved him, the world did, indeed, seem wonderful.

Tourists are always arriving. Moms, pops, little kids disembark from buses shuttling in from asphalt lots, from outlying Resorts, from Gerald knows not where. Having entered at a gate marked STAFF, he turns to survey the multitude. Lines two hundred faces long snake toward twenty turnstiles as more faces arrive. And that is just here, this minute at the Kingdom. There are four other Theme Parks, always crowded when Gerald attends. Animal World. Moviewood. Fun City. And Nations of the Earth, Gerald’s favorite. All of them fabricated on forty-seven square miles of scrub land in central Florida. Uncountable yards of concrete, millions of tons of Italian marble, North African tile and tropical hardwoods, global stone, American steel. Not to mention the sheetrock and plastic. The Parks and Resorts employ thousands and generate profits in the billions. Talk about making the desert bloom.

And in this mass of humanity, Gerald Chimes knows no one. MM Management itself holds him at arm’s length. All decisions come down from windowless offices at the company’s low-slung compound at Kissimmee Corporate Park. Gerald’s liaison, a pleasant woman of indistinct provenance too-aptly named Dolores, returns his calls promptly and, when Gerald appears at her office, invites him to sit.

“Are you pleased with your situation here?” Dolores asks as Gerald settles into an armchair. What can Gerald say, except “Yes”? His permanent suite is spacious, its view of the man-made lake calming, its liquor cabinet well-stocked, its housekeeping staff impeccable if not so friendly. “I do have a request,” he begins, and Dolores’s eyebrows arch. “That is, I have been wondering, or rather feeling, lately, a need, or rather a desire, for, well . . . companionship. Female companionship, if I may say so.”

Dolores smiles. “Of course you may. And of course you do. We have been wondering when you would broach the subject.”

Gerald just gazes at her, his heart feeling crowded and tight.

“We are concerned with your welfare, Mr. Chimes,” Dolores says. “With your—dare I say, ‘happiness’? I am concerned. In every sense. What you think, how you feel. What your plans are for the future. Everything matters to us.”

The armchair, Gerald notes, is upholstered with the same blue and gold fabric of stars and wands and sorcerer’s hats found wall-to-wall in his permanent suite. Flattered, grateful, he holds his breath. He will not weep, he won’t.

“A woman’s company,” Dolores goes on. “Of course. What could be more natural? It is, I believe, for most men the second part of happiness—happiness itself having seven parts, as sages tell us.”

Gerald nods. He does not know the seven parts of happiness. “I was thinking, or perhaps hoping is a better word,” he says, clearing his throat, wiping his eyes, “to become acquainted with a Princess. Jasmine, if possible. Or Belle, with whom I expect to have much in common. Or better yet,” he says, surprised by the thought, “Cinderella. She is, after all, an orphan, and would understand—”

Dolores sighs, stopping Gerald’s mouth. “Cinderella, needless to say, is married to Prince Charming. Far be it from me to presume, but I doubt their conjugal relations are what some persons call ‘open.’ Then, too, there is her name.”

“It doesn’t—I don’t—”

“Unfortunate, that her mother chose so morbid a compound. The sense, I believe, is ‘Ash Girl.’ Yes, very unfortunate. But there it is. Surely it would distress you. Yes?”

Gerald shrugs. “I was hoping to know her real name.”

“Oh, Mr. Chimes, we can hardly tell you that!” Dolores is almost laughing, not at him, exactly, but almost laughing nonetheless.

“Why not?”

“The magic, dear man! The adventure, the fantasy, the Technicolor dream! Think of all you would lose in that moment when, having wangled the dear girl out of her powder-blue gown and sported with her the whole night through, you awoke in a soiled bed beside a rumpled sexmate. Pleasure is evanescent. A Fairytale is Forever.”

“Well, actually, I—” Gerald catches himself. Discussion, he realizes, is futile. It goes deeper than corporate policy, straight into the marrow of their bones. His bones, Dolores’s bones, the bones of every Princess, past, present, and future, who floats up Main Street with a hundred retainers madly grinning in her magical wake. He shakes his head, says, “Do you have someone in mind?”

Now Dolores does laugh at him. “I appreciate your impatience, Mr. Chimes, truly I do.” She lifts a sheet of paper from her desk and hands it to him. Gerald has not noticed it, the paper, before. Where has it come from when he wasn’t looking? “If you save that date, at that place,” Dolores tells him, “you may be sure of meeting someone who will be happy to know you.”

Two days later, Gerald Chimes sits in Italy shortly before noon, at one of the white wrought-iron tables-with-red-umbrellas that give this pavilion its Old World charm. He orders Pellegrino, specifying two glasses and slivered lime. While he waits, Gerald surveys the Great Lagoon, still and glittering under a clear sky. Across the water is Canada, its log fort and beaver-hat trading post seeming misplaced in the semi-tropical heat. Norwegian Village is desolate, its Viking Mead Hall and Nordic Gift Shop shoehorned between China and Japan. Tourists flock to Morocco and Mexico, Italy and Greece. Olive- and chestnut-complected attendants nod and bow and smile in English. It is a sham that innocence and good intentions make charming. Everyone seems pleased.

When Gerald turns his head again, he sees her standing in the shadow of Pisa’s Leaning Tower as if daring the half-scale replica finally to fall. She is younger than he has expected, a dozen years younger than he is, at least. A certainty of failure rushes through him. Although fit from walking, Gerald is no Adonis. This young lady, seeing his dwindling hair and baggy eyes, will merely laugh and with her hand, whisk whisk, dismiss him. Oh, Gerald has survived worse and how can derisive rejection truly hurt, but still. Dolores must play a deep game, indeed.

The waiter returns with glasses and ice, sparkling water and a pair of silver tongs. Something about the way he delivers these, the flourish or half-bow, catches the woman’s eye. She raises a hand, a small hand, Gerald sees, and waves. He waves back, stands and motions her forward.

“Hello,” she says, a tight smile pulling her lips awry. “I’m Ruth.”

Of course you are. “Gerald,” says Gerald and offers his hand, which she takes. They shake, holding on a second longer than Gerald usually does. It has always felt strange to him, shaking a woman’s hand. It’s what men do. Something nicer should be possible with a woman. A little kiss, just on the cheek, seems right. But a kiss between strangers, even on the Italian pavilion, is dicey. Ruth might let him, if the kiss were quick and light and dry. Or she might shrink from him, or she might smack him. The uncertainty is inhibiting; the handshake suffices. They sit.

“Sparkling water?” says Gerald.

“Yes, please,” says Ruth.

“Ice?”

And she nods. Gerald tongs cubes from the thermal bucket into their glasses. He twists the cap off the Pellegrino and pours. He offers slivered lime and Ruth nods. Gerald tongs two disks each into their drinks and slides hers over.

“Thank-you for meeting me,” he says.

“I should say the same,” says Ruth.

“Oh, the pleasure is all mine.” He is about to add some inanity along the lines of so happy to enjoy the company of a beautiful young lady but bites his tongue. It might sound phony, for Gerald can see that Ruth is not beautiful, not quite. Her nice nose is a little too broad, her good teeth are not perfectly straight, her shoulder-length hair is that shade of brown catty women call mousy. But her skin is unblemished and her hazel eyes are round and wide open. She is pretty, Ruth is, to Gerald more than pretty enough.

When she lifts her glass, Gerald sees the diamond on her finger, backed up by what appears to be a platinum wedding band, also adorned with diamonds.

Is this his cue to stand, bow, and walk off? Gerald grips the chair’s iron arms and sits tight. They’re just talking, they haven’t done anything wrong. But what stratagem has Dolores put in play?

“Your rings are beautiful,” he says.

“Thank you. I’m afraid I’m a bit vain about them.”

“No need to apologize.”

“Did I sound apologetic? I didn’t mean to.” She sighs. “Dolores says I should stop wearing them.”

This statement, to Gerald, does not make immediate sense. “I assume we know the same Dolores? Dolores Marqurolle? Inscrutable woman. I cannot imagine what she intends.”

A mingled expression—surprise and concern, Gerald thinks—crosses Ruth’s face. “I’d assumed you knew,” she says. “That Dolores explained.”

“Am I right in thinking you are friends? Of course she means well, bringing us together.”

Ruth looks past him as she says, “Dolores has been helpful, and very kind.” She glances at Gerald, again looks away. “It is simplest to say that I know her as you do.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. Very sorry. How—”

“We’re not supposed to talk about it.”

“Yes. Except we already know.”

“Someone might hear.” Ruth’s voice is steady. Both hands hold the glass.

“Of course, we can never be too careful.” This comment seems absurd even as he says it, not to mention second-level hurtful. “Still, it is a legitimate topic—for us, or rather between us. If we hope to know each other, I mean.”

Ruth says, “We mustn’t expect too much. I guess that sounds discouraging. I don’t mean to be. Just sensible—‘realistic,’ I think is the word people use in our situation.”

Our situation. Gerald swallows his reply. How many people does she figure are in their fix? Then again, Ruth might be right. Maybe MM World is full of them, a mute army of widows and widowers, parents bereft of children. Drifting among attractions and pavilions and gently exciting rides. Trying to forget. Gerald remembers his water, delicate bubbles dissipating in the heat, and swallows half of what his glass still holds, dissolving ice bumping his upper lip. “Realistic is fine,” he says. “I suppose it’s our only choice. Notwithstanding the illusions that surround us,” and with his hand traces the arc of Nations around the Great Lagoon.

Ruth laughs. “Touché,” she says, as if she actually knows the language. “Also shocking, I suppose most people would think.”

Gerald nods. “Fair enough. I have to admit, I let them take me in hand.”

“Did you?”

“Oh yes. I woke up in the hospital and there they were. A young man and two young women, not one of them more than twenty-four or -five. And not Americans. Foreign-born, I mean, and speaking lilting English. Mr. Chimes, hello, we are very pleased to find you looking so well today. Ta-da, ta-da, tee tee tee tee tee tee tee, ta-da, ta-da. That kind of thing. Very pleasant to hear, so musical and soothing. And they were beautiful, their faces so smooth, complexions like caramel, and very white, straight teeth, and their hair glossy black—sleek. They looked sleek, the three of them, tall and slim and perfectly turned-out, speaking in beautiful English of tragedy and loss and the fated turnings of Fortune’s Wheel. By the time they finished I loved them. I wanted to rush at them with my arms and eyes and mouth wide open. But I was wrapped up like a mummy and couldn’t move.”

Ruth is looking at Gerald as if she thinks he’s joking. “That would have been startling,” she says.

Gerald laughs. “I suppose it would. But they would have known how to handle it. They were special. Obviously highly intelligent. Obviously well-educated. Terrific poise. I was embarrassed.”

“You had just suffered terrible trauma. You deserved special treatment.”

“Yes, but to have those gorgeous young people at my bedside like ambassadors, or . . . expert apologists, I guess I’d call them, when of course they themselves had done nothing wrong and were besides so clearly superior as human beings—” Gerald stops himself. He is saying too much, talking too long. Why can’t he shut up about himself and draw Ruth out? Then he thinks of one thing more. “I don’t know if Management planned it, but I felt humbled.”

“My, my. Tried and true. A Company man.”

“I appreciate what they’ve done for me. Being here”—and he gestures at the clever buildings, the authentic facsimiles and scaled imitations, inviting Ruth to share his gaze, as if not just the fabricated pavilion and brick thoroughfare and ivory-white Tower slanting in the sun but the air itself illustrated his sentiment and justified it—“is really pretty great. They’ve made it easy, Dolores and her emissaries. As easy as could be.”

“Yes, well, it was the simplest choice,” Ruth says quickly. “To stay. And the terms could not be better.” Before Gerald can assent, she hurries on, “Anyway, I never visit Animal World, which I never liked to begin with. So it isn’t as if I’m constantly reminded.”

“No doubt that helps.” He wonders if something is wrong with him. He visits Nations of the Earth every day, weather permitting, and never feels shaky about returning to the scene. Just there, on the pier abutting Germany, Lorrie and Sherman and little Francine were standing with their backs to the Lagoon and waving to the camera while fireworks ignited on a barge and shot into an indigo sky. It is all on the video Gerald will never review: the barge breaking its mooring in a sudden squall, a minor tempest of gale-force wind, and drifting their way and slamming the pier, and pressurized canisters exploding into the wind-driven air. On video it looks as if it’s raining fire, which, in a sense, it is. When Gerald dropped the camera and ran to smother the flames, to try to, it, the camera, chanced to land with its lens focused on the end of his, Gerald’s, life. Tilt your head ninety degrees, he told MM Legal, who were trying to watch stone-faced, and you will see more than you can bear.

He tells Ruth none of this. She already half-knows and anyway has been through something like it. Given her remark about Animal World, Gerald does not want to know more. Except he has to know more. They need to speak of it. Of them. The lives they lost. It will be worse than difficult, more than horrible. Both by promise and by choice, Gerald never mentions how he lost his family.

“Still,” Ruth says, “it’s in the past. There’s no reason we can’t try to be happy.”

They try. Dolores, consulted, tells Ruth and Gerald they are on their own. Except: “We rely on your discretion. We trust you to preserve the dignity of personal grief. Do what you will, by all means what you must. But do, say, share all in private.” Meaning, in his permanent suite or hers.

Ruth and Gerald say what must be said. They tell each other the core story of their dissimilar lives. Gerald describes the night of fireworks and wind, his own role as cameraman, the severity of his burns. He reveals details he does not remember until he puts them into words, frames them as sentences, casts them as paragraphs describing three human beings, his beloved, burned beyond recognition, burned into anonymity, their familiar faces and smiles and unforgettable eyes erased. “People say ‘burnt to a crisp,’ ” Gerald says, uncomfortably, unsure, trying to take the edge off, “without thinking what it means.” His eyes fall to the carpet spread wall to wall. The blue and gold pattern is understated, repetitive, ubiquitous. It is something, nothing. Part of what is.

“It’s horrible,” Ruth says. “I’m so sorry for you.”

“And I for you.”

They are seated in armchairs facing the doors that open on the balcony of Gerald’s permanent suite. Through the plate glass, cleaned daily, they watch airbursts of red, of silver, of royal blue, and showers of shimmering white, and whistling golden pinwheels that moment by moment light up the satin sky. The reports arrive a moment later, making the glass vibrate.

“After a while it gets annoying.”

“They overdo it,” says Gerald. “One’s senses go numb.”

Tracers shoot skyward and explode. Glittering tendrils of celestial fire swoon down. It is the bravura performance staged nightly on the courtyard that fronts the famous Castle.

“I don’t see how you bear it. Every night! Isn’t it upsetting?”

“Oddly, no,” says Gerald. “I could have ended them. Just as you put a stop to free-range predators.”

“It would have taught them a lesson if you had. Made it a condition of your silence.”

“That option remains open. Bad publicity stops hearts at Corporate Park.” Gerald recounts how Management covered the Accident by making it seem like an illusion, a part of the show. They were devilishly quick; you would have thought they planned for catastrophic failure and sudden death. He isn’t, he explains, sure of the details, what with his confusion and grief and dire injuries and shock on many levels, but it seems Entertainment came up with robotron imposters on the spot, dressed more or less as Lorrie and Sherman and little Francine and Gerald himself had been, mere moments after the ill-fated Chimes family vanished. Abracadabra, POOFF! And, oh, nothing has happened, all is well, isn’t it wonderful. Talk about magic. The pristine condition of the Parks and Resorts, the miracle of maintenance that keeps every dwarf and Donald and mechanical deer looking brand-spanking-new, is a banality in comparison.

Ruth nods at his story, so close to her own. The quick intervention, the plausible fix. Smoothing out wrinkles in time and space. It is a concerted effort of infinite ingenuity bringing major resources to bear. Impressive in effect and essentially dishonest. “And we help it happen,” she tells him. “We agree to step through the looking-glass, led by the hand.”

“That’s true,” Gerald says, “but it’s all to the good. It’s the best choice we have.”

“Is it?” says Ruth.

In the weeks that follow, Gerald Chimes escorts Ruth Elliott on outings to Fantasyland, Adventureland, Tomorrowland, Frontierland; to premieres and filmfests in Moviewood; to casinos and dance clubs in Fun City; to nothing at Animal World, which they have tacitly agreed does not exist. They promenade daily around the Great Lagoon, never touching, an arm’s length of radiance separating their bodies, their hands. This same space sits between Ruth and Gerald on the wood-slat seat, painted red, of MM World Railroad, which they board once a week to make the circuit of the Kingdom. Likewise on the seats, painted green, of the bateaux mouches in which they float between Gerald’s permanent suite at the Boardwalk Hotel and Ruth’s seclusion at Beachfront Villas. Within the privacy of their rooms they kiss, not seriously. They do not venture on anything more intimate. When Gerald reaches for her, Ruth moves away.

He is disappointed. He is not surprised. Ruth is young and pretty. She deserves someone better. Gerald, now forty-one, is starting to look old. A detailed reckoning courtesy of the over-bright mirror in his ceramic-tiled bathroom yields hints of the geezer in the wings. The bags under his eyes are huge and getting worse, while his eyes themselves seem each day to sink another millimeter into his skull. Gerald shaves fastidiously yet the permanent shadow that stains his upper lip seems to grow darker while the skin itself has, paradoxically (or maybe not), a grayish cast. Hoary, hirsute old man. He hasn’t started to stink yet, he doesn’t think so, but assumes that’s next. Until then there is the scarred skin of his arms and torso, which Ruth has not seen but probably can picture and doubtlessly does not want touching her, or to touch. Doubtlessly.

Who is he kidding? Any woman who really knows him will find him repulsive.

Ruth Elliott, he figures, is a lost cause. Only their tragedies keep them together, if together they may be said to be. And how long can it last, the charade of normalcy while concealing one’s pain, of being emotionally on eggs as they walk from, say, the Hall of Presidents to Ariel’s Grotto, both of which they have already seen, many times, and have lately seen together, again? They have seen it all, Ruth and Gerald, truly seen it all, throughout the Kingdom and the Parks. There is precious little for them now in the confected world.

They start spending their days mostly in France. At the café by the river, they drink coffee all morning and, beginning at lunch, some very special wines. Weeks pass without their visiting the Kingdom, its Main Street choked with children and blighted by smiles. Soon they are often apart. Ruth begs off with a headache, fatigue, uninterest, and holes up in her suite. Receiving her messages, so thoughtfully relayed by the Front Desk, Gerald winces. That his used-up appearance fails to draw Ruth to him is no worse than he expects. Gerald assumes he will also fail to dissuade her from doing what he feels sure she is about to do. He has learned long ago that he himself can do nothing, that love and caring and due vigilance are flimsy bits that a brisk wind blows away; and so he knows he cannot stop her and anyway does not want to, despite being unsure about how her departure might affect him. Will Management hold him that much closer? Will Dolores Marqurolle deliver Princesses to his permanent suite? Or will Management cancel their concord, confiscate his minted ingot and, ready to brave all consequences, steeled to take what comes, cast him out? It seems almost not to matter except that it does. Gerald Chimes does not want to be cast out, he does not want to be on the receiving end of trouble or to cause it. If he had to name it, what he mainly wishes is peace. Peace for himself and everyone near him, with his neat clothes and quiet life under the Florida sun.

Christmas Week the Parks are packed. Tourists from all over the globe mass at turnstiles, step on each other’s toes in line for rides, for food, on restroom queues. The lobby of the Boardwalk Hotel is lumbered with a super-size gingerbread house large enough for a child to sit in. An O-gauge replica of MM World Railroad winds through a miniaturized landscape of winter mountains and frosted conifers laid atop a platform not unlike a stage. A spruce tree as tall as the ceiling is high dominates the sitting area opposite the Front Desk, itself festooned with evergreen garlands embellished with red velvet bows. It is decorated, the tree, with white lights and red ribbons and shiny blue and gold orbs made of eggshell glass. All together it gives Gerald the melancholy, but to require its removal seems churlish; everyone enjoys it so, like the carols played in continuous medley over resonant speakers hidden everywhere. Even walking to France, beside the serene river, over the interlocking bricks, Gerald hears music: “Jingle Bells,” “Silent Night,” “Deck the Halls,” “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear.” In the Kingdom they parade up Main Street from the Railroad Station to the Castle, that grinning mouse in a Santa suit with his sidekicks done up as elves, accompanied by a high-performance version of “Here Comes Santa Claus” detonating in the crystalline air. Gerald, crushed by multitudes, unable to escape, covers his ears. He is disinclined to complain. It is Christmas Week. The folks deserve their fun, these paying guests who cough up top dollar to support Gerald’s residency and permanent perks. Everyone smiles. The children are happy.

Oh, where are those expert young persons when he needs them? He thinks they were Pakistani or Indian, possibly one woman was Egyptian, with their flawless complexions and white teeth and sleek hair. Beautiful English. Gerald believes they would know what to say to him now.

On New Year’s Eve, Gerald Chimes and Ruth Elliott share an early-bird dinner at Hibachi House. He is smartly decked out in silk tie and cummerbund and new Armani tux, she is luminescent in pearl-gray Dior, her ordinary hair professionally coifed. All for show. They are casual with each other now, although tonight’s mood is not lighthearted. Gerald knows what’s coming, which is that she’s going, before Ruth says, “Gerald, there’s something you deserve to know.” She is leaving tomorrow, she tells him, by dawn’s early light. Giving up her permanent suite, surrendering her minted ingot, shaking Never Land’s pixie dust off her shoes.

“I’ve thought it over,” she says, nudging cold fish with chopsticks into a soy sauce pool, “and I can’t let it happen. I can’t let them buy me off with room and board, even at five-star quality.” She nabs a slab of yellowfin, dips it, pops it into her mouth.

Gerald waits for her swallow, then says, “Don’t you like it here?”

“I like you fairly well,” she gives him, making him beam, letting him think, Maybe tonight, just once, “especially when you’re dressed like that. But this place gets on my nerves.”

“There’s no end to the fun you can have,” says Gerald.

“It’s impossible to be cheerful all the time,” Ruth says. “If I stay in bed all day one of Dolores’s small fry is ringing the phone every twenty minutes to ask how I’m doing.” She sighs. “It gets oppressive.”

“The past week has been ghastly, I admit.”

“Bloody nightmare. Kids and Christmas trees. Do they maybe want to kill us, too, you think?”

Gerald shrugs. “It’s a matter of life goes on.”

She thinks about it, seems to, chewing tuna. “Not for me. Not like this.”

“I’ll miss you,” Gerald says, but really, he won’t. Company is fine and it’s nice to share dinner but without sex there isn’t much to miss. The truth is they have little in common, he and Ruth, other than something they would rather forget, and a broken heart. On the outside they would never have dated, assuming they would have met, which Gerald figures they wouldn’t, because how could they, and why? Of course not. It has all been a mistake, a well-intentioned error brought about by a tragedy. Two tragedies, and what are the odds of that? So of course it could never last or even be, of course she is leaving, of course, of course.

Ruth, busy with salmon roe, says, “You’re sweet, Gerald.” Not, I’ll miss you, too; not, Let’s keep in touch, sometimes I’ll visit. “I’ll tell you something,” she says, “for future use,” and Gerald thinks, Here it comes. My feeble biceps and thinning hair. My rancid breath and body odor. “You should get out,” she tells him.

For a second Gerald thinks she means Hibachi House, her presence, the Japanese environs of this Park. He almost says something about wanting to finish his food, then understands.

“Whatever for?”

“It’s not a real life. Breakfast in France. Lunch in Mexico. Dinner in China. Living big and paying for nothing. Having nothing to do.”

Oh dear, Gerald thinks. So serious, so earnest, so very young. “My real life is over,” he says, stating a fact. “I don’t want to do anything—I don’t need anything to do. The last time I tried to do something, three people died.”

“You couldn’t save your family and your answer is to give up?”

It sounds sad, the way she says it, but Gerald isn’t sad, not here, not tonight, the last night of the year. “I don’t think of it as giving up,” he says, knowing it will not satisfy her. But he doesn’t have to satisfy her or even listen to her talk. She is leaving and not coming back.

“What do you call it?”

“I don’t know that I call it anything. I’m just a man trying to get along.”

“You do a lot better than get along. You live like a sultan.”

“Without the harem, yes,” he says, hoping it stings.

“Well, you don’t need a harem, exactly,” she says, and that’s that.

“Regardless,” says Gerald, “it’s nice here. The different Parks, the plush Resorts and great restaurants. It’s a happy place. People come here to be happy, and you know what? They are.”

Ruth glares at him not just with disappointment, Gerald perceives, but anger.

“How can you?” she whispers. “Your children died here.”

“Yes,” says Gerald. “And nothing can change that.”

Ruth shakes her head, shuts her eyes. He knows what she’s thinking. Find a new thing to care about. A project, a cause. Devote himself to a greater something. Meaning, more important. To have the satisfaction of playing a part. Another part. A different one. As if any of it could replace what he’s lost.

“Aren’t you angry?” she hisses.

It is a question Gerald has asked himself. He has never found an answer that seems quite right. Magic words elude him. He says, “People make mistakes. Accidents happen. Holding a grudge, nursing resentment like a hunchbacked troll—that does not make me happy. In fact, I would be miserable. I do not want to be miserable.”

“Well, then—aren’t you sad?” Ruth asks, pleads, in a voice that betrays her.

Gerald is not sure what he wants to say, other than he’s had enough and would like to move on. The faintest of smiles crosses his face. “I’m trying not to be. Staying here seems like the best chance I have.”

“I wouldn’t have thought so. You speak to no one.”

“Conversation, ah . . .”

“You won’t look at the children.”

“Well,” Gerald says, as if telling a secret, “that’s right. And maybe I’m wrong. But my kids loved it here. That seems like a reason to stay.”

They finish their meal, flash their ingots, engravings gaudy in the lantern glow, and step outside into late December’s early dark. Near a bench overlooking the Great Lagoon, Ruth turns to him. She holds Gerald’s shoulders as she kisses his cheek.

“Goodbye, Gerald. You’re a nice man. I hope it works out for you.”

“And I for you.” He kisses her lightly in turn.

“If you ever reclaim your freedom, look me up. I’m sure we’d be friends.”

Gerald, sure of no such thing, says, “An excellent inducement, thank you. I will keep it in mind.”

Ruth’s smile says she knows. “I’m leaving first thing tomorrow. We won’t see each other again.”

“Yes,” says Gerald. “I understand.”

In the morning, bells are ringing to greet another year. Gerald Chimes, fresh from sleep, rises at a godly hour and prepares to meet the day. Blue twill trousers and gold-on-blue striped shirt, long-sleeved, for even in Kissimmee winter nips the air. Gerald dons a blazer, navy blue with pewter buttons, lightweight and refined. By the time he gets to France, Ruth Elliott, he guesses, is aloft over Georgia en route to the place she hasn’t named. He eats his croissants, drinks his coffee, waits while the sun climbs high enough to warm him. He quits France by bateau mouche and journeys to the Kingdom. Gerald saunters up Main Street, remembering, forgetting, trying to stay with what he sees, the moment he is living and the moment after. He loves the Penny Arcade and old-time Emporium, the Confectionery Shop and classic Ice Cream Parlor, ironwork façades painted creamy white. Young couples linger at windows, childless, relaxed. Young families surge past him, stroller wheels humming, hot on the trail. Gerald nods and smiles. No one seems to see him.

He skirts the Castle and follows the path and in the heart of Fantasyland finds Cinderella’s Carousel, which he has long known is there. Its lacquered deck is larger than a stage. Solid oak horses, carriages, and chariots are enameled in lifelike colors and bear emblems, crests, and coats of arms, fittings of polished brass. Gerald watches it turn. Half the horses rise and fall in rhythm with the calliope. Others are still. Children laugh and smile, hold on tight, while parents take pictures. It is perfectly safe. Soon the Carousel slows, the music ends, the children dismount from chargers, coursers, trusty steeds, scatter across the gleaming planks and clamor through the exits. Other children enter through a separate gate and dash for favorite mounts, having been here before.

The bell rings, the music plays, the Carousel starts to turn. It is by its nature endless, as long as children live in a world that lets them imagine what a perfect day might be. A place such as this, on just such a day. Gerald Chimes, dry-eyed, watches them deep in the heart of a happiness only children feel. Some children. These children, here. In love with the turning moment, laughing as if the ride will last forever.

Copyright © 2019 by John Lauricella.