A young family’s visit to a former stop on the Underground Railroad stirs up disquieting ghosts of the past.

“THE BIRTHING ROOM” is Second Prize winner in our 2018 Fall/Winter Fiction Contest.

1850

When the white lady tells her to hold the baby, to name it, so its little soul will go to Jesus, Corabel says, “No.” She can’t bear to touch the child, to be its mother even for a second. Best to begin forgetting right away. But the white lady insists. They will pray. So Corabel’s shaking arms receive the girl-baby, wrapped in a torn white sheet, streaked with blood. The baby’s skin is blue-grey, but her features are even prettier than those of Missy Sylvia, her half-sister. At the white lady’s urging, Corabel utters the hymn, the phrases distracting her from the lump of flesh in her arms, growing cold. “Birdie,” she says, naming the child after the cook in the big house.

It’s a mistake to say the name out loud. The sound of her own voice, speaking of her own child, breaks Corabel apart.

2018

What should have been a three-hour drive from Park Slope, Brooklyn, to Monterey, Massachusetts—with hardly any traffic since they left early Friday morning, before Olivia’s first nap—wound up taking five. Rob is annoyed but knows to keep his mouth shut, deferring to Galen in all things pertaining to Olivia and her innumerable needs. And Olivia, never having traveled such a great distance, needed to nurse not once, not twice, but thrice along the way.

Olivia finally fell asleep twenty minutes ago. Galen will stay with her in the car with the windows open for another forty minutes to make sure the baby’s nap is sufficient. Rob can bring their things inside, Galen says, as long as he’s careful not to slam the trunk.

Rob is careful not to slam the trunk, though there’s a Rob in an alternate universe who does slam the trunk, slams it very hard indeed. Rob envies Alternate Universe Rob, who does not tiptoe around his wife, who expresses dissent, who gets laid occasionally, whose Galen, he imagines, did not lose herself post-childbirth. Rob is guardedly hopeful about this trip, however. He thought he saw light in Galen’s eyes yesterday while they packed.

Galen booked the trip before the baby was born. Unaware that she would require an extended maternity leave, she and Rob coordinated vacation time from the hospital where they both work—Galen as a psychologist and Rob as a heart surgeon. Rob wanted to spend a week at the beach, but Galen insisted upon an Airbnb in the Berkshires. An old red farmhouse that had been a stop on the Underground Railroad. When it comes to anything pertaining to black history and culture, Rob defers to Galen too. Before they married, they agreed to embrace all their heritage: Galen’s African American along with Rob’s Dutch and Scotch-Irish, for the sake of their future children.

Touting the house’s amenities, Galen assured Rob that he could swim in a nearby lake, adding with a wicked grin, “And sun your pale ass all you want.” What Rob really wants is a return to normalcy. How he misses that grin of hers.

Rob is halfway to the front door when he hears Galen’s “Psst.” As he turns, she blows him a kiss and mouths, Thank you. Rob smiles, thinking that there is no one in the world as beautiful as his wife.

When he lets himself into the house, Galen lowers the window of the car to take in the fresh country air, floral with a note of rotting wood. There’s an antique wagon under a tree which someone has turned into a whimsical flowerbed, full of petunias and geraniums. The front lawn is long and full of wildflowers. Picturesque, but Galen will have to check the baby daily for ticks.

Olivia gurgles in her sleep and Galen shuts her own eyes, enjoying the birdsong against a whistling New England breeze. The light dims through her eyelids, as clouds blanket the sun, revealing a momentary image of the house in darkness. A flash of motion inside the windows, like flickering candle light. A piercing cry—a young woman’s voice. Galen shakes her head. An instantaneous dream, real enough to be a memory. She’s stepped into and out of some narrative of her brain’s own making, now completely lost.

The gloom is haunting her again. Galen shakes her head, fighting it as whimpers herald the end of the baby’s nap. Galen stretches, steps out of the vehicle and gathers her child.

“Hello!” An older, greying blond woman is walking toward the car, followed by Rob. “I’m Maxine. You—must be Galen.”

They’ve spoken on the phone, but the family’s Airbnb profile is a photograph of burly, sandy-haired, russet-bearded, green-eyed Rob. That was Galen’s idea. Not to use her husband’s whiteness per se, but to break ground if necessary, to open doors that might otherwise slam shut. It follows that Maxine, the owner, had no clue Galen was black. The older woman transitions from surprise to comprehension, then extends a hand, which Galen shakes.

“Oh! And this must be Olivia,” Maxine says. “How precious!”

The tension evaporates as Maxine coos over the baby. Olivia is precious. Galen’s ticket to acceptance with white mothers—old, young and in-between. No one dares ask if cinnamon-hued Galen is the barely-tan baby’s nanny. Galen’s posture, her Ivy League diction, her relaxed and styled hair, her designer activewear, the sizable diamond on her hand—these preempt such an error. But presenting so impeccably drains her. At home, in private, Galen implodes.

Rob pipes up, “Maxine’s been showing me around. I told her you were the history buff.” He takes Olivia from her and encourages Galen to take the tour.

Maxine starts with the upstairs: the bedroom where Rob and Galen will sleep, the baby’s room right across the hall, and an enormous, lemon-scented, modern master bathroom with a stone basin and matching shower. Downstairs is a living room with a plush, green velvet sectional and mounted eighty-inch television; an expansive kitchen with granite countertops and subzero everything else.

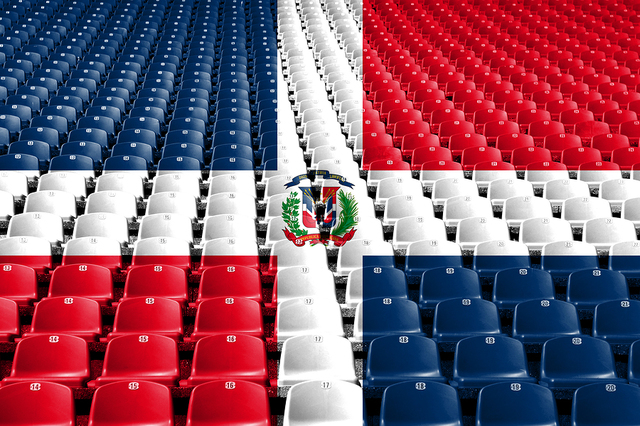

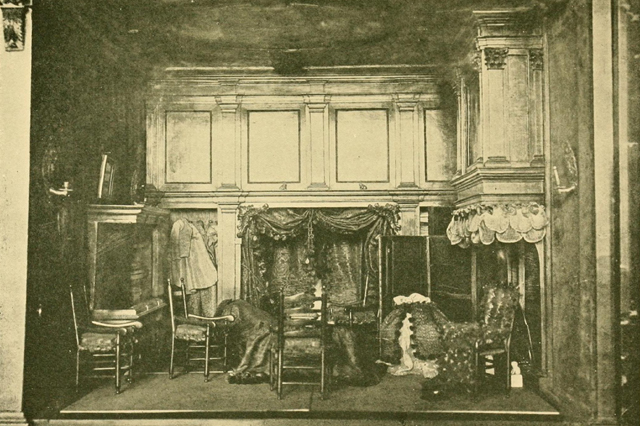

The rest of the ground floor has been preserved in its 19th century glory. All is dark wood and wrought iron: a library with brimming shelves; a birthing room with a fireplace, a rocking chair, a spinning wheel, and a cradle. Galen gives the latter a push and it creaks pleasantly, as if remembering babes of yore. She smiles, imagining an old grandmother, one watchful eye on a sleeping infant, spinning by the fire. Quaint iron-handled tools hang from the mantelpiece: a poker, a wire brush, a scoop for ashes and a woven leather-handled knife.

“I’m interested in the history of this place,” says Galen. “I’ve read that it was part of the Underground.”

“Ah,” says Maxine, smile brightening. “But the runaways weren’t hidden here. It was too close to the road.”

Galen bristles at the word “runaway.” As if her ancestors were teenagers giving their parents the slip. “The freedom seekers,” she corrects Maxine gently. “Where did they hide?”

“Out in the root cellar. In the middle of the property, about fifty yards up the hill. I can show you if you like. Or, if you’d rather unpack now, I can point it out and you can take a peek at your leisure.”

Galen nods. “I would like to get settled.” She rocks the cradle again, enjoying the sound. With all the slick gadgets they have for babies these days, there’s something about antique, hand-crafted things.

1850

Corabel barely remembers her mother, neither her name nor face. Only that she was known as “Massa’s favorite.” Corabel was five when she was sold away—her mother’s punishment for being so favored. Corabel understands now, with her caramel skin, she was the living marker of Massa’s infamy. His Missus demanded Corabel’s sale to the Madsens. She was sold again at eleven, taken to the Durham plantation in North Carolina.

Here she works in the big house like her mother did, assisting Birdie, the old, mute cook. Durham is a widower, mean and harsh, feared by his children as well as by those he owns. He favors amputation as a punishment for his wayward property. He cut out Birdie’s tongue as a penalty for gossip: sharing the secrets of the house with field hands who were purported to be planning a mutiny.

Since the age of fourteen, Corabel has been Massa Durham’s favorite, cursed like her mama. Corabel hears the whispers of the others who work in the big house. They hate her for being soiled by Massa’s fearsome touch. They resent the favors he bestows on her when the mood strikes him. Carriage rides. A new dress. A lighter workload, mostly attending to Sylvia, Massa’s youngest child and only daughter. Sylvia is just five years younger than Corabel herself. They are two motherless, lonely girls who—in another world, another day—might turn to one another for friendship. Instead, Sylvia is spoiled, demanding and full of complaints. Always, Corabel is to blame for her misery.

Worst of all is the cost of Massa’s favoritism. His hands, his coarse mouth. The violent thrust of him in the darkness. The blows he delivers when she cries or bleeds or dares to turn away. The hatred in the eyes of the other house slaves. Only Birdie shows Corabel kindness. The cook saves her soup, dries her tears and offers a sympathetic glance, an occasional soft embrace. But the old cook has no words to cheer her.

Bringing rations to the field hands’ cook house is Corabel’s responsibility every Saturday, just after dawn. The field hands accept the baskets she brings—of cornmeal, molasses, flour, lard, peas and meat, everything measured within the ounce—with a nod, an occasional grunt, but no word of acknowledgment, camaraderie being out of the question. But none of the field hands spits at her or glares at her the way the others in the house do. Corabel knows some of their names, faces and stories. She’s heard gossip around the house about plots to flee North foiled by slick drivers and other spies. She knows of Blind Zachariah, once caught reading, and Lame Joe, who got the hamstrings torn in both legs as a consequence for running. She knows Little Annie, two fingers cut off when she was caught pilfering food. Wintertime rations couldn’t sustain Annie’s six children. In the end, two starved and the rest were sold, leaving Annie cut by Durham in more ways than one.

By Corabel’s sixteenth spring, she is with child, though her slight build and the way she ties her apron conceal the fact from others in the big house. One early Saturday, after dropping off provisions at the fieldhouse, Corabel is startled to find Little Annie blocking her path, arms akimbo. Annie is built like a young boy and barely comes up to Corabel’s chin. Corabel wonders whether the trousers she wears belonged to one of the sons who got sold. Annie is deep brown, purple brown, with sloping, hooded eyes and tiny braids peeking out from under her headscarf. She holds out her three-fingered hand, a tiny, cotton pouch resting in her palm.

“Here,” says Annie, voice a raspy whisper. “Take it.”

Corabel’s arms are full, holding the empty basket. “What is it?”

“Nettle leaf.” Annie drops the pouch in Corabel’s basket. “For you. For the baby.”

Corabel gasps. She’s told no one since she began counting too many days since her last blood. “How did you know?”

“I have a sense about such things,” says Annie. “Your walk is different.” Corabel is flattered to think that anyone has noticed her at all, let alone pick up a change in her walk. Annie tells her to drink the leaves in boiling water. “It’s what I did.” She drops her eyes and moves on down the path.

It happens again the following week, the week after that and the next: Annie has something new for her, some herbal preparation to assist with her condition. Corabel finds herself looking forward to the encounters, the closest thing to a friendship she’s ever had. On the fifth week, Corabel empties her basket at the cookhouse, then makes her way in the direction of home slowly as usual, giving Annie a chance to catch up with her. Before Annie can appear, strong arms grab Corabel from behind, nearly knocking the wind out of her. A hand covers Corabel’s mouth, preventing her from crying out. Day is just breaking as she’s dragged down a narrow lane and into a dim, dank cabin. Corabel hears men’s breathing, men’s voices; terror quickens her heart.

“Don’t hurt her!” Corabel recognizes Little Annie’s voice and relaxes. “Let her be.”

Once released, Corabel turns around, eyes adjusting to take in the images of two men—field hands, judging from their worn clothes and postures. Annie stands by them.

“What do you want?” Corabel demands.

“Your help,” says Annie. “We mean to run.”

2018

Galen watches Rob’s powerful back and shoulders emerge from the water, then vanish again, arms pumping in rhythm, commemorating his glory days on the Princeton swim team. They were lucky to arrive in good time and good enough weather for a swim their first day. Halfway across the lake, Rob pulls himself up on the anchored raft and waves at her, dripping hair haloed in sunshine. Galen waves back then shifts the beach umbrella to make sure the slumbering Olivia is safe from the sun’s afternoon rays. Rob dives back in. In no time he’s hovering over her, dripping lake water, grinning his wide, freckled grin.

“You should take a dip,” he says. “I’ll watch Livi.”

“Too cold.”

“Bracing,” Rob corrects her.

“Really.” Galen casts a skeptical eye out over the lake, glistening onyx in the afternoon light. She rises and slips off her blue and white caftan, treating Rob to a gander of her mostly-returned-to-pre-baby physique in its lavender bikini. She glances at the baby and steps toward the water’s edge, toes mingling with tiny pebbles and lakeweed in the icy brew.

Galen shivers but goes forth. Rob used to tease her about being an indoor, city girl. Then, when the despair set in after Olivia’s birth, he stopped teasing altogether, treating her gingerly, always on guard. She can sense his longing for the Old Galen, who was quicker with a biting comeback than tears. To show that she’s still here, Galen flashes a smile back at him and squares her shoulders. She takes a running dive, ignores the chill, and swims all the way out to a tiny island about fifty feet past the raft.

The surface is more marsh than land. In the center is a grey-barked cypress tree that begins with one thick trunk and branches out into two separate entities. Galen walks around the tree in search of a spot where the ground is more solid. Halfway around, she sees a shape whip past then disappear into the lake with a splash. An animal, she thinks: a beaver or possum. Galen approaches the site of the splash, where the water is shaded and murky. She hears Rob call.

“I’m fine!” Galen calls back. “Just checking something out!”

On the far side of the island, there’s an ancient rowboat washed halfway ashore. Water laps erratically at its base. Something is alive down there. Venturing closer, Galen peers under the rowboat’s raised hull, eyes adjusting to register a woman’s head and neck. Galen masters her racing heart and leans closer. The woman is submerged up to her shoulders, wearing a full cloak which floats around her. She has tiny, dripping braids that stand out from her head. The sun glints off the water, illuminating the woman’s dark brown face, the fire in her eyes. The woman raises one hand, revealing the stumps of two fingers.

Galen’s brain fires suddenly; she knows this woman. Not her name, but her. The memory is incomplete—nothing specific like a classmate from grad school—but there’s recognition nonetheless. Galen has a momentary compulsion to join the woman, to huddle beside her in the shadowy pool. But she blinks, and the woman is gone.

Galen scrambles to the place where the boat drops into the water. She peers underneath again, then wades out, searching the weeds.

“Gay!” Rob’s voice. “What’s happening?”

Galen can’t speak. Unable to make a shred of sense out of what she saw or didn’t see, she steps around the tree to show Rob that she’s in one piece. A handful of clouds are circling the sun now. It must have been a trick of the light, she thinks, an optical illusion. Though Galen can still see the face of the small woman, her identity just out of reach. Putting aside her misgivings, Galen forces herself to swim back to shore.

“You’re shaking.” Rob has a towel ready when she reaches him. Galen takes the baby, but cannot lose the image of the woman’s eyes gazing from the shallows.

“Are you okay?” Rob repeats.

“Just cold.”

Rob cannot know.

1850

Little Annie and the two men, Caleb and Josiah, need things for their journey that only Corabel can acquire for them. A pot of grease from the stables that Annie will mix with herbs to disguise their scent and throw off the dogs. A knife for protection. Rope—Corabel doesn’t know what for. Maybe some bread or biscuits till they can get to somewhere that might offer a meal. And, with hope and luck, a compass. There’s a silver one that Massa keeps on his writing desk. Corabel can picture it sitting there, but she knows there’s no way to take it without him noticing. He’d know right away it was she who’d done the stealing. No one else comes in his room. Just her. To clean, and when he wants her there.

“I’ll do my best,” Corabel tells her new friends. But are they friends? Soon Annie and Caleb and Josiah will be gone from this place and Corabel will be left alone with the silence of Birdie, the sneers of the other house workers. And her baby, which won’t be hers at all. It will belong to Massa to do with as he pleases. Corabel shudders imagining herself growing big, then pushing the child into a cold and dreadful life that hates its mother, will hate it too. Another dread is that the baby could come out white, which would be worse. On the Madsen plantation, there were whispers about a high yellow boy raised in the big house, believing the Massa’s barren wife was his mama. His own mother, who worked in the house, was his nanny, nursed and cared for him till he was grown. She took his truth to her grave.

Corabel gathers the things they need slowly. Now that her condition is no longer a secret, Birdie has given her old clothes that bag and sag, easier to conceal things. She finds a rope in the cellar and hides it under her apron. Saturday morning, Corabel tucks it under the rations in her basket. Each week, she delivers something the three need for their journey. Little Annie squirrels everything away beneath the floorboards of her cabin.

Mostly, Annie, Caleb and Josiah want information about Massa’s plans. When he’s traveling, things relax on the plantation. Everyone exhales the breath they hold in his watchful, brutal presence. His sons Thomas and Peter are lazy young men, spoiled like their little sister Sylvia. They take everything for granted, including human property. Best to run when Massa’s gone.

With business at hand, being taken care of, there is less conversation with Annie. No more talk about how Corabel is getting on as the baby grows inside her. Corabel senses Annie’s gratitude, but companionship—such as it was—fades. She is useful to Annie, to Caleb and Josiah, nothing more. Just as she is useful to Sylvia, to Massa.

On laundry day, while Sylvia is busy with lessons, Corabel stokes the fire to keep the water hot as her fellow house workers, Maggie and Etta, wash the sheets, speculating about the upcoming Cornhusking celebration at the neighboring Collins plantation. Massa will be in Alabama, leaving Thomas and Peter in charge.

“Massa Tom—he’ll let us go for sure,” says Maggie, nodding agreement with herself. “He says we work best when we get our time for enjoyment.”

“His daddy doesn’t subscribe to that,” says Etta, eyes downcast, a glow in her high cheekbones. It’s common knowledge around the big house that she’s got her eye on one of the Collins’s stable hands.

“His daddy doesn’t need to know,” Maggie chuckles, giving Etta a playful swat. “You’ll get to see your sweet Ronnie. Don’t you worry.”

Maggie explains how it’s all going to unfold. Massa Thomas and Massa Peter and little Sylvia will drive their carriage to dine as guests of the Collinses. The slaves from the Durham plantation will make the brief pilgrimage to the Collins property on foot while the four overseers ride alongside, keeping watch over the lot. There will be music, food, whisky—pleasures rarely enjoyed in the daily life of a Durham slave. Best of all will be the husking contest. Anyone who finds a red husk will win a prize.

Corabel listens to their talk, takes in every detail she can. Little Annie and the men will want to hear about this. Most likely, they’ll run the night of the husking.

Though Corabel is right beside them, neither Maggie nor Etta pay her any mind. When she first came in with the wood, Maggie eyed her belly with a grunt but said nothing, didn’t offer to lighten her load or tell her not to carry so much at a time. Now Maggie leans away when Corabel adds to the fire, pulling her skirts clear of the grating.

They go on chatting as Corabel stokes the fire. Etta never looks her in the eye, never speaks to her—not even to ask for more wood or a sturdier paddle. As if it’s a sickness she can catch, Corabel thinks. And why, she wonders, did Massa choose me instead of Etta, who’s just as light, just as slim, with hair as long? Etta would be as much of a prize sitting in the back of Massa’s carriage underneath a parasol. Corabel shudders, remembering how—before she started to show—she was trotted out like a thing, stared at, groped, breathed on by Massa’s old men friends. A yella princess. How they’d laugh, pinch and poke. How still she had to remain, taking it all, lest she get whipped at home.

“You’re lucky,” Corabel says aloud to Etta, stabbing at the flame. Etta raises her wide, brown eyes.

“What’d you say?”

“I said you’re lucky it’s me instead of you. You know you are.”

With that, Corabel sweeps out of the room to see if Sylvia’s tutor is still working with the girl. Perhaps she’ll listen in, snatch a small piece of learning.

Late at night, Corabel is in the tiny room she shares with Birdie, downstairs off the kitchen. Her eyes are open, staring through the window at the moon. It’s harder to sleep now that there’s a baby inside her, growing toward the miserable life outside. If it’s a girl—to be raped, pawed, and fouled. If it’s a boy—to be whipped, sold or otherwise taken from her.

Now Corabel hears a familiar thumping in the hall outside, a crash and a clatter as Massa—drunk and stumbling—upsets the order of the kitchen. Corabel smells his breath before he’s inside the room. Birdie stirs but can’t do anything to stop what’s coming. He’s on Corabel now. By the light of the moon, she can see the veins in his neck throbbing. The angry set of his jaw. The force of his rage. He’s lost at cards. Gotten swindled or cheated. In any case, she’ll bear the brunt. He can feel her dread, her revulsion. He shakes her, slaps her face, then tears her robe. In no time he’s inside her, the terrible thrusting, grunting like a beast. Corabel bites her own arm to keep from crying audibly. He finishes, slapping her again and stumbling off.

Clouds drift in front of the moon and Corabel rests her hands on her belly, praying for the baby to stay as small as it is, to die inside her.

2018

Dinner is over. They grilled the fish and vegetables they’d bought on the way up. Olivia is playing quietly on her mat while her parents have a drink on the screened back porch. Citronella candles keep a check on the mosquitos that find their way through the aging screen. The back yard is a sprawling meadow, flanked by gardens near the house, woods at the furthest end. As the shadows lengthen, frogs sing from their perches alongside a brook that runs through the grassy turf. Rob touches his Sam Adams to Galen’s glass of Sauvignon Blanc. She’s not supposed to drink on the meds, but one can’t hurt.

“Happy summer.”

“Happy summer,” she replies. “It’s beautiful, right?”

Rob doesn’t take his eyes off hers. “Right.” He dares to slip a bare toe under the hem of Galen’s filmy sun dress. She reenacts a giggle, like the old days, and gives his foot a half-hearted swat.

“Later,” she says. “If Livi sleeps tonight.”

“Big if.” Rob takes back his wandering toe. Bringing up the topic of their sex life usually backfires. Galen gets flustered, defensive, explaining how the meds kill her libido, how self-conscious she feels about sex while she’s lactating. Rob always says he understands. Though vis-à-vis nursing, there seems to be no end in sight, even though Olivia is beginning to eat solid food now. In any case, Rob is banking his good behavior, hoping that one day, very soon, Galen will be done with the meds, lactation will end, and he’ll reap the rewards in hours upon lost hours of connubial bliss. If only Galen would lay off the skimpy dresses.

Rob says, “Did Maxine give you the full tour?” Note how he’s changing the subject, giving her space.

“Yeah,” says Galen. “I didn’t get to the root cellar though.”

“I did,” he says. “Kind of creepy. Dank. I can’t imagine having to hide in there.” He takes a swig of beer and looks out at the garden. Trying not to think about sex.

“I want to go,” Galen says, sitting up suddenly.

“Yeah?” Rob beams at her, incredulous. “Really? Now?” By go, he assumes she’s thinking what he’s thinking.

“Now,” she says. “I want to see the root cellar. You put Livi in her BabyBjörn and I’ll go find some flashlights.”

So, Galen is not thinking what Rob is thinking. Not by a long shot. Awash in disappointment—that Galen’s sudden enthusiasm centers around checking out the root cellar rather than, well, him—Rob drains his beer.

“Let’s wait till morning,” he says. “It’s too buggy now. What if Livi gets bitten?”

Not even their baby’s welfare can dissuade her. “I’ve got netting in with my hiking stuff.” Galen gulps the remainder of her wine and dashes into the house.

Five minutes later the family is crossing the dusky meadow with lanterns—Rob, wearing Olivia, mosquito netting stretched over the infant carrier. The root cellar is at the far end of the property, where meadow meets woods. Rob’s lantern illuminates a ramshackle wood-and-steel door wedged into the side of a hillock. As he lifts the latch and creaks open the door, a moist-earth smell rushes out. Galen raises her lantern over the mouth of the cellar, making out a narrow stone stairway.

“You stay out here with her,” she tells Rob, and begins descending the steps. Her lantern’s beams bounce against the grey stone wall. Moisture and age have rotted away most of the shelving that once housed carrots, turnips and sweet potatoes that sustained the inhabitants of the house through long Massachusetts winters. She sees the unmistakable imprints of Rob’s sneakers on the dirt floor, left over from his tour. Galen follows them down the corridor till the ceiling slopes down, too low for Rob to stand. She proceeds around a bend as Rob calls her name.

“I’m fine!” she calls back, stepping deeper inside. The shelves look sturdier back here; one holds a mortar and pestle, another a collection of tin canisters. Galen imagines the escapees holing up down here, nibbling seeds and roots to survive. She’s just reaching out to touch a clay urn when her lantern flickers. No good to be this far from the doorway with no light to find her way back.

“Rob? I’m coming back! My battery is low!”

The only response is a gust of wind and a dull thud. “Rob?”

With the light she’s got left, Galen makes her way back along the passage, around the bend to the stairs, only to find the door shut.

“Rob!” She dashes up the steps to push it back open, but it’s latched. Calling her husband’s name, Galen pounds and pounds at the heavy wood structure in vain. The lantern flickers recklessly, then dies out. Galen panics in the pitch darkness, knocking and calling furiously until the futility sinks in. She lets herself slide down to sit on the step and take stock of the silence, complete but for her own breath and racing pulse.

All at once she hears “Hush.” An implausible sound, uncannily like a whisper. It can’t be, Galen tells herself, it cannot be a voice, but a chance breeze that got trapped inside somehow—never mind the scientific impossibility of such a thing.

“Hush.” Again. Galen shuts her eyes, aware that fear is playing tricks on her, recreating what she’s spent so much time reading, imagining, and wondering about: The people who made the journey North. What they were like. How it must have felt to hide here, to wait fugitive, praying for a clear sky, a bright moon and stars to travel by unmolested. Who were they?

“Be still.”

“Who’s there?” Galen cries out.

“Hush,” comes the whisper again. Hush. Be still. You’ll get us killed! More voices layer on top of one another, coming faster, blending together. Hush. Be still.

Galen covers her ears and buries her face in her knees. But a sharp pain seizes her abdomen. She grabs her belly, distended and hard, like the fish was bad. Or the vegetables. How crazy is this? She’s so frightened she whimpers. No. No. No. But how insanely real it seems.

Galen quiets her mind, makes herself present, aware only of the sensations of her body, like in yoga class. Slowing her breath, being mindful of the pressure of the stone stair against her body, her thin dress with just a jean jacket thrown over it, the sudden cold. The pain, the fierce bloating. She recites the simplest meditation mantra: I am breathing in, I am breathing out. I am breathing in, I am breathing out. Galen notices her thoughts, lets them pass by without judgment. But oh—the pain! And the voices. She hears them still: Hush. Be still.

“I am breathing in,” she tells herself emphatically. “I am breathing out.”

Yes, breathe. That’s it, baby, that’s it. Nice and slow. Breathe in and out. You gonna make it. Gonna be okay. Hands, small, rough, but still soothing on her forehead, her arms, her taut, tight belly. The high, whispered voice. Breathing in and out along with her. You gonna be okay. The panic eases if not the pain. Galen relaxes, accepts the touch of the hands, reclines with her head in the other’s lap, eyes still closed. “I am breathing in . . .”

How many minutes, how many hours go by?

“Galen? Gay?” Rob is shaking her gently. “Honey, what’s going on? You’re scaring me.”

He pulls her up from the cellar floor, accidentally swinging Olivia sideways in her carrier.

“What happened?” Galen says, brushing the dust from her jacket. “Where were you?”

“Right there at the top of the stairs,” he says, shifting the baby back into position. “Where else would I be?”

Behind him she can see the stairway, the open door at the top and a glimpse of treetop against sky, nightfall not quite complete. Galen realizes: it’s she who has gone. She who has returned. With scarcely a minute lapsed.

“You okay, hon?” Rob says.

“Sure,” she replies. “My lantern died. It freaked me out.”

“Understandable.” Rob puts an arm around her as they mount the stairs. “It’s a little too spooky down here. Even with a working lantern.”

Back in the house, Galen nurses Olivia once more before bed. Once the baby is settled in her crib, Galen crosses the hall, kisses Rob goodnight and allows sleep to consume her. She dreams of heads in the water and of whispers in the cold darkness.

1850

Cornhusking Day draws to a close with the Durham slaves meandering home, overseers leading the way and bringing up the rear on horseback to make sure everyone is accounted for. But the riders are drunk and it’s dark between the torches they hold aloft. No one notices Annie, Caleb and Josiah slip away, one by one, into the woods. Only Corabel knows their secret, which she promised to keep or die. But now she fears for their lives more than for her own. For their sake, she hopes never to see them again.

At the celebration, she danced with Josiah. He grinned at her and said how well she moved despite being with child. For the first time, Corabel noticed how wide his smile was, how his eyes sparkled as he laughed and spun her around. Josiah clapped his hands in time to the wild music of the fiddle, and Corabel was aware of not wanting him to go. He read her thoughts. Glancing around for eavesdroppers, Josiah leaned in close.

“You could join us.”

Her eyes widened. Corabel shook her head, hands on her belly. “Not like this.”

Then a horde of other men, with a chorus of noisy guffaws, splashing the corn liquor from their cups, surrounded him, absorbed him, pulled him away.

And now, walking home, Corabel doesn’t join in the singing of the others, just tries to relive the dancing, Josiah’s hands—one wrapped around her own hand, the other at her waist. Corabel tries to hold the image in her heart to give her peace when things get bad.

“Girl.” She hears a male voice close by. “Girl!”

She turns to stare into the ghostly face of Thomas Durham. Just four years Corabel’s senior at twenty, he is lean and towering. Massa Tom’s jacket is askew, ascot untied and hanging. “I’m talking to you—hear? You mind me, now.”

His words slur with liquor. Corabel takes in his unsteady gait, considers bolting out of his reach, weighs the risk of retaliation. But Massa Tom is in sounder shape than she thought. He grabs her arm and pulls her toward him, claps a hand over her mouth and yanks her into the dark woods.

He’s powerful, strong as his father if not stronger. Liquor whets his rage the same way. Obscured by the gloom and trees, they stumble along, Corabel wincing, whimpering under Thomas’s thick palm. At last, he pushes her back up against a broad, solid oak, tears her dress open and forces his way in. Corabel shudders with fear and disgust, presses her eyes shut as she does with his father, praying for it to end.

Suddenly, the whoop of a screech owl pierces the air. But Corabel knows: it’s no owl. She feels them out there—Josiah, with his wide smile, Annie with her rough but kind directives, anxious, watchful Caleb—calling to one another with their secret signal. And Corabel does what she’s never done in her life. Fights. She opens her lips against Massa Tom’s stinking hand, separates her teeth and clamps them down hard on the bone of his thumb. Thomas howls in agony but doesn’t let her go, so she doesn’t let up either. Keeps biting down, even as he forces his other hand against her throat, pressing the air out of her.

They struggle together and fall, Tom on top of Corabel, one hand still around her slender neck. She panics, reaching breathlessly behind her for a branch or something to beat him back with. Her hand finds a stone, cool and broad, embedded in the ground. Corabel utters another prayer and the earth gives way. One-handed, with the borrowed strength of a guardian angel, Corabel brings the stone up as hard as she can to meet Tom’s head with a crack. He releases her, falling back, unconscious. Corabel stares at him, breathless, unable to move at first. Now her gaze lands upon a slim, gleaming silver chain dangling from his pocket. Corabel pulls out Massa Durham’s compass and runs as fast as she can without a backward glance.

She follows the screech owl cries till she comes upon the meeting place: an abandoned boathouse by the swamp. The others take in her ragged, swollen form in the moonlight.

She tells them, “I’m coming too.”

They walk all night and all the next day, counting on the Durham brothers and all the overseers to be too hungover to notice their absence till late. Fortune had Missy Sylvia spending the night at the Collins’s home or the girl would have known Corabel was missing right away. Still, they reckon it’s Sylvia who sounds the alarm. Sylvia who they’ve got to thank when the dogs come. Annie’s salve is powerful though; it throws off the beasts. The four fugitives sink low into the swamp till the sound of barking subsides.

For three days, relying on luck and prayer, they manage to put distance between themselves and the Durham place. When the bread runs out, they hunt for roots and berries. They travel by night, checking Massa’s compass in the moonlight, following the stars. They keep tight by the swamp, hiding by day.

“Before long,” Little Annie says, “we’ll find us a swamp town where they’ll take us in for a spell.”

Leading the way deeper into the mossy wet, Caleb explains that there are colonies of runaways and Indians living free, hidden in dwellings around the swamp. Corabel can’t imagine how such folk could settle this close to plantations without being caught. But on the fourth day, they come upon one such establishment, in a remote spot concealed by a thick halo of mist. The inhabitants, various shades of black and brown, speaking dialects Corabel hasn’t heard before, give them food, shelter, several days’ rest, and the courage to move on. They continue along their way, relying on members of other such colonies to sustain them, to guide them north, beyond the reaches of the swamp.

In exchange for the silver compass, a free colored man in Norfolk helps them gain passage on the Boston-bound cargo ship where he is employed. Massachusetts is a free state, the sailor tells them, but with no papers they’ll be returned if caught.

“Meantime, you all stay below in the hold.”

None of them has been on a ship before. They keep silent and out of sight, as best they can, amongst the sacks and barrels, the rats and other vermin. But the lurching, pitching, and rocking echo inside Corabel’s gut. Again and again, the free colored crewman smuggles her up to the deck, where she heaves the contents of her stomach, mostly bile, over the side. Each time, Corabel prays that the baby will make its exit along with the matter she expels. But the child clings fast inside her, stubborn and determined.

Corabel can’t guess how many days pass before the ship finally docks. She and her compatriots remain below deck till the colored sailor introduces them to a white man whom he calls “Conductor Dodd.” The latter apologizes before chaining Caleb and Josiah together. They’ll travel by carriage, Dodd explains. If they run up across catchers, the ruse will be that they’re headed north for construction labor. The women will be hidden under the boards of the carriage compartment in blankets.

After a day’s journey, something goes wrong. From their hiding places, Corabel and Annie hear shots which spook the horses. The carriage picks up speed, then goes rolling, reeling and over on its side. Corabel’s arms cover her head, then her belly, as she’s bounced and flung inside the compartment. Now the carriage is still, but here come more shots and the shouts of men. Then silence.

“Annie?”

“Hush up!” Annie whispers close by her elbow. Then adds in a sharp hiss, “You keep still!”

Their hearts pound like drums, breath comes in short pants. But they keep still. They make no sound. Hours later, Annie forces open the compartment to find the black of night and a sliver of moon. No house nearby, just the road with woods on either side.

“Come on.” Little Annie pulls Corabel by the sleeve and the two emerge to find the carriage resting in a gully, smashed up. One horse lying on its side, dead. Conductor Dodd, same state. Caleb and Josiah gone.

It’s just the two of them now. They make the next leg of their journey on foot together, hiding in the woods and in abandoned sheds. Dusk finds them in the garden of a church, where they’re spotted by an old white man in a black, wide-brimmed hat.

“Make haste,” he hisses at them, beckoning. He provides a meal, rest for one night and advice. In the morning, the man directs them to a pond where they’re to wait for a boatman.

“Take heed,” he tells them. “Hunters are everywhere.”

It’s midday when they find the body of water, more bog than pond. A half-sunken rowboat offers refuge during their vigil. They lie inside, feet at either end, heads side by side, gazing up at a blue sky where corpulent clouds dance a reel before a golden sun. Corabel swats at a fly and lets her cloak slip to the base of the boat, enjoying the breeze. Now she dares to lift her head out of the boat, to look out over the glistening water.

What swells inside her is hope—for something: a life for herself, maybe for this baby too. The notion emboldens her to reach one hand into the water. As her fingers touch the surface, a surge of tingling energy compels Corabel to dive in. She swims, pumping her bare arms and legs, the water caressing her flat and childless belly. After a bit, she pauses, treading water, looking out ahead at the shore, where a white man stands holding an infant. Corabel doesn’t know him at first; his face is uncharacteristically calm, almost pleasant. Then recognition sinks in and terror strikes her heart.

She panics, body flailing helplessly as the reverie ends. Corabel is back with Annie, big with child again, clumsy. As she reaches toward the water, she unbalances the boat and tips them over. Annie’s startled cry, their scrambling and splashing, gain the attention of a dog, whose barking brings on the shouts of men.

“Get down!” Annie gulps air and submerges herself. Corabel follows suit and there they crouch, in the shallows beneath the upturned boat, sneaking breaths, shivering, occasionally listening, waiting for evidence that they’ve escaped discovery.

2018

The thing about being reached for, reached for by Rob, is how claimed it makes Galen feel lately. Before the baby, she didn’t mind. Their touching, claiming, reaching for one another was balanced, mutual. And while she loves him still, and finds him as beautiful as always, it exasperates Galen that Rob never gives her the space or opportunity to reach for him. No sooner does she set down the baby than she meets his hungry, craving eyes, followed soon after by his reaching arms. Male arms, white arms, claiming their due.

Galen didn’t think of him that way before—as White. He was only Rob, representative of nothing but himself. Their commonalities—their shared wit, aesthetic, values—outweighed their contrasting skin tones. But Olivia’s arrival, along with the baby’s fair skin, hair and light eyes, changed something in Galen. Wherever she goes with her child and husband, she feels the weight of other people’s scrutiny and unuttered questions. If she were one of her patients, Galen would force herself to examine her feelings about this. Instead, she amasses them in a cloud of undefined anguish. Medication barely takes the edge off. Galen thought it would be easier here, away from busy Brooklyn. But this house, with its past, makes it worse. All she can think of when she looks at him is that his forbears owned hers.

“Are you okay?” Rob’s constant query.

“I’m fine,” she tells him. “I just need some tea.” Galen gets out of bed as quietly as she can, avoiding a loose floorboard that might resonate and wake the baby. Livi is in her crib across the hall, but the two-way monitor is on.

“I’ll be up soon,” Galen tells Rob before he can offer to join her.

In pitch darkness, she feels her way downstairs to the kitchen, makes her tea and takes it to the birthing room, where she settles in the rocking chair. She shuts her eyes and rocks, inhaling the mingling aromas of chamomile and old, smoky wood. Time lives here in this space. History, death, memory—they’re all contained in the preserved section of the house. Galen considers herself: an affluent, black woman psychologist married to a white cardiothoracic surgeon, vacationing in the very spot where an enslaved woman died for freedom. And yet, Galen wonders, how is my marriage—my family—anything but a point along the historic continuum that began with masters and the women they owned? Quaking with rage at the implausibility of true change, Galen looks around for the legendary spirit, her eyes dancing past the leather-handled knife.

“What must you think of me?” Galen addresses her fore-sister. “In the end, we are no different.”

1850

Corabel lies on the dank earth of the root cellar floor, head in Annie’s lap. They waited all day and half the night for the boatman, who brought them to the big house just a mile up the road. The white lady gave them hot stew, dry clothes, and brought them here to the root cellar where they’ve been ever since, waiting till it’s time to move on.

Now, each time the pain hits, Corabel bites her lip to keep from crying out until she can hold in the sound no longer. The tightening grips her innards, too strong for silence.

“Hush!” Annie whispers, hands on Corabel’s belly. “Be still. It’ll pass.”

Corabel howls again.

“Girl, hush now!” warns Annie.

“I can’t help it,” Corabel says.

“You’ll get us killed if you don’t hush up!”

“I’m sorry,” Corabel says. “I can’t stop it.”

“Baby’s coming.” Annie knows too well. “We have to get you to the house.”

“It’s not safe,” says Corabel. A day earlier, the white lady, fear in her eyes, showed them a poster with their names and descriptions—promising a reward for their return. Corabel cries out once more and Annie says she’ll go ask the white lady for help, at least for hot water and towels. Annie slips away, up the stairs, and crosses the grass in the darkness. But the white lady tells Annie no. It’s not sanitary to birth a baby in the root cellar.

“Tell her to be silent,” the white lady says of Corabel. “The slave hunters are everywhere. But we have no choice. We’ll take the risk.”

Which is how Corabel finds herself on the bed in the birthing room by the fire.

Corabel shudders as she stares into the blue-lidded face of the child who looks like Missy Sylvia, but prettier. She prays as the white lady bids her, then hands the child over and turns toward the wall. She feels a scream coming up from within her chest, erupting into the tiny room, shaking the very frame of the house.

“Hush!” says the white lady, tears in her own eyes. “None of that, now. You mustn’t make such a noise!”

How long Corabel’s howling goes on, she doesn’t know. She keeps her eyes shut and floats on the sound, willing her body to dissolve into the mist of her grief and wild thoughts. The noise draws the catchers, who have traced her from the Durham plantation, following the lead of Massa’s silver compass. First come their loud, deep voices, the hateful words and cusses. Next come big, broad, heavy hands on her body. Hands like Massa Durham’s, Massa Tom’s, white men’s hands, pulling, grabbing, taking their due. She sees his green eyes widen as he rips her clothes from her body, her body from her heart.

Corabel loses sight of the white lady, of her cold, little girl-baby, Birdie. Bitterness absorbs every notion of the future that she’s dared to entertain, every scrap of hope. There is nothing inside her but hate, nothing outside her but green eyes and cruel, broad, white hands that are the cause of every evil in this world. Rage makes Corabel stronger than she’s ever been; her small, brown hands, invincible. She fights even harder than she fought with Thomas in the woods, wrests a dagger from the man’s belt.

2018

Finding himself alone in bed at 3:15 a.m., Rob makes his way downstairs to find Galen asleep in the rocking chair, empty teacup on the floor beside her. Gently, he lifts his wife, meaning to carry her back up to bed. But Galen opens her eyes and panics, disoriented. She screams, eyes wide, pushing and punching at his chest with her fists.

“Gay! What are you doing? It’s me!” But her screaming drowns out his words.

1850

Finding her strength at long last, Corabel meets his green gaze with fury in her own. The dagger is one with her arm, driven by her will and refusal to be taken again.

With a final howl, Corabel buries the blade into a soft target, allowing the warm blood to spill. Corabel laughs aloud, knowing she’ll never have to mind another white man. She makes her own choice: gripping the knife with both hands, she turns it inward, sets herself free.

2018

Early the next morning, Maxine arrives with extra bath towels. She rings the doorbell as a courtesy, waits what she considers to be a reasonable amount of time before letting herself in. She hears a creaking sound from the birthing room and discovers little Olivia, sleeping peacefully in the antique cradle, which is somehow rocking smoothly from side to side. Maxine steps closer, puzzled. Only then does she look past the cradle and spot the tipped-over spinning wheel.

And there they are.

Read our Q. & A. with the author.

Copyright © 2019 by Lisa W. Rosenberg.